It has been a number of years since I last looked at how the CRTC deals with telecom service in high cost serving areas. In 2020, I reminded readers of an under reported consequence of the Commission’s landmark 2016 Telecom Policy determination.

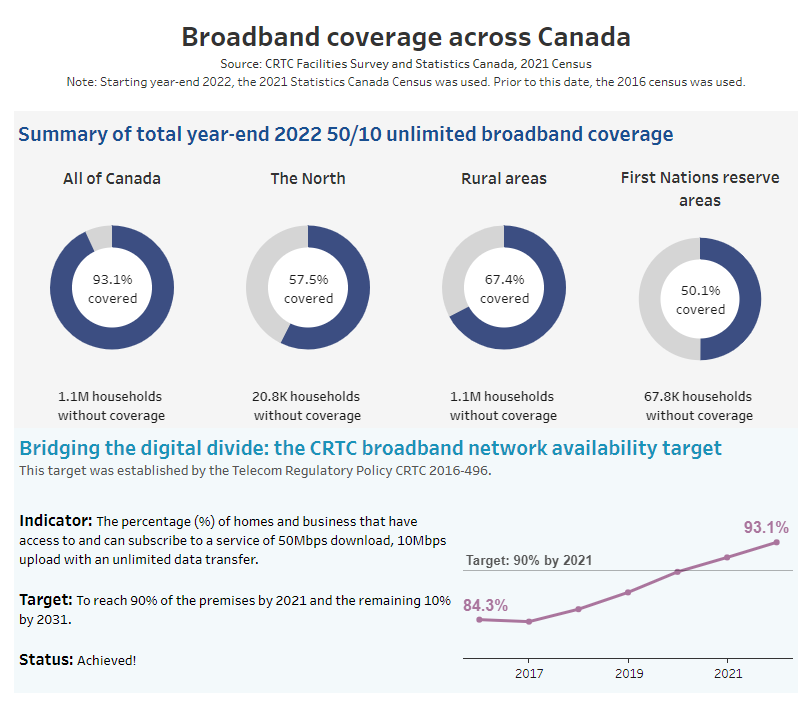

At that time, the CRTC created its own broadband subsidy fund – a pot of money that seems to be easier for the Commission to collect than to distribute. But, the regulator also announced, “the Commission will begin to phase out the subsidy that supports local telephone service.” The CRTC swapped out a program that provided ongoing support for all high cost serving areas, in favour of awarding one-time payments to specific winning projects. Although the CRTC’s Broadband Fund duplicates other federal and provincial government programs, the cynic in me blames the allure of handing out oversized ceremonial cheques or appearing at ribbon cuttings.

That is relatively old news. Why bring that up today? Good question.

There is a CRTC proceeding underway that I found interesting. Perhaps you will as well.

In British Columbia, there are 8 communities served by three very small telephone exchanges with a total of 110 residential customers and 5 businesses: Leading Hill and Espinosa in the Tahsis exchange; Nemiah Valley and the Xeni Gwet’in First Nations in the Alexis Creek exchange; and, Red Lake, Tranquille Valley, Heller Creek and Green Stone Mountain in the North Kamloops exchange. North Kamloops is a forborne market, meaning that telecom services there are not regulated; in Tahsis and Alexis Creek, services are provided under regulated tariffs. Tahsis is located about 200 km from Courtenay; Alexis Creek is about 100 km from Williams Lake; and North Kamloops is in an extremely mountainous region 50km from Kamloops.

As such, these communities are connected to the TELUS backbone network using microwave radio links using the 3500MHz band. The radio systems being used in these communities are outdated. The equipment is no longer supported; the manufacturer (SR Telecom) went bankrupt 15 years ago. As if that wasn’t enough, the spectrum is being reallocated by ISED. Despite an intent for the 3500 MHz spectrum plan to recognize how it was deployed for rural fixed applications, service in these communities is a victim of the band moving to mobile service.

All this to say, TELUS notified customers early in the New Year that their phone service was going to be discontinued. The letter from TELUS indicated that customers would be receiving a cheque for $1400 as compensation. The amount was seen as sufficient to cover the installation and up to one year of service fees for an alternate service provider operating in the area.

TELUS voluntarily offered this compensation because it was guided by related situations of regulated services withdrawal. In particular, the financial compensation is comparable to the amounts that the CRTC has recently ordered other carriers to compensate customers impacted by scenarios where such carriers have applied to the CRTC to withdraw a regulated service in its entirety due to obsolete technology or increased costs that make the service uneconomic.

Note that TELUS is giving the financial compensation to all affected residential customers, even if they might have Internet services from another provider. For customers who already have Internet services, the $1,400 is well above what they will need to pay to add VoIP services for one year.

As of May 1, 88% of customers had already cashed their cheques. More than a quarter of the customers have already migrated off TELUS. In its application, TELUS says that in one of the communities, there is only one remaining customer using the TELUS service.

As TELUS wrote to the CRTC, the business case to deploy fibre facilities to these communities is not viable. Each are located very far from the nearest local exchange, requiring significant expenditures to build transport facilities via terrestrial technology. TELUS said that constructing terrestrial transport networks is simply not feasible in the short or medium term. “Such construction would require TELUS to obtain land use and access rights over Crown and First Nations lands. It is TELUS’ experience that obtaining such rights often takes years, because of the need to conduct consultations with various agencies and stakeholders.”

And as you have read on these pages countless times, mandated wholesale fibre doesn’t help the business case. It makes it even less attractive. TELUS included precisely such a dig in response to one of the CRTC’s interrogatories:

Unserved fibre communities such as these underscore why wholesale fibre-to-the-premises (“FTTP”) mandates, such as those under contemplation in Review of the wholesale high-speed access service framework, Telecom Notice of Consultation CRTC 2023-56 (“TNC 2023-56”), are not sound policy. There are still many rural and remote communities that lack FTTP access. Regulatory mandates worsen the business cases for future FTTP deployment. As a result, FTTP deployment in rural and remote communities would be most at risk, given that the business cases there are already marginal. TELUS noted the especially adverse impact on remote and rural communities of wholesale FTTP mandates in its Intervention in TNC 2023-56.

Keep in mind, there is already at least one other service provider operating in the area. Customers are not being left without any options for telecom services.

Last month, the CRTC asked TELUS to file a Part 1 application to set out:

- TELUS’ proposal for how it intends to respect the Commission’s policies and regulations governing the disconnection of local exchange service, and

- alternate options that would be available to TELUS for serving these communities (for example: obtaining a license from the new spectrum licensees, using alternate spectrum, or implementing other technologies).

The Commission noted that ISED has extended permission for TELUS to continue to use the spectrum until March 31, 2025. ISED noted that “This authorization only applies to existing legacy 3500 fixed point-to-point links and will not grant protection from interference, nor can operation interfere with other licensees in the area. TELUS will be required to cease operation upon reports of any interference from the operations of these links in the area.”

The CRTC has stated a belief that TELUS has an obligation to serve communities in its operating territory.

In a competitive world, what does an “obligation to serve” mean? TELUS responded that it is a federally-incorporated company that has authority to provide telephone and other telecommunications services throughout Canada, but it has no legislative duty, either under its incorporating statutes or the Telecommunications Act, to provide its services to any particular community or in any particular part of Canada.

TELUS wrote in its application:

Under the current legislative and regulatory framework, Commission approval is not required for a scenario where an incumbent telephone provider like TELUS faces the loss of facilities necessary to continue provisioning home phone services generally. There is, however, a process to apply for CRTC approval in analogous situations involving the withdrawal of regulated services provided pursuant to a specific tariff item. The process requires that customers be notified, substitutes be identified, and reasonable compensation in the form of a one-time payment be provided to affected customers. TELUS has proactively taken these constituent steps, plus more, in this extraordinary scenario where the continued provision of service by TELUS has been rendered impossible absent the construction of an entirely new network.

The application lays out an alternative. TELUS says the Commission can authorize (and subsidize) new construction to support fixed or mobile broadband under its Broadband Fund, furthering the CRTC’s goals to bring broadband coverage to rural and remote areas. “Though TELUS is not subject to a regulatory obligation to build broadband facilities,” the application provided details for options for two of the communities.

There is a fundamental difference between having the authority to provide telecom service, versus having an obligation to provide such service. I’ll look more at the issue of the obligation to serve next week.

At the core of this regulatory proceeding is a need to understand the economics of providing telecom service in high cost serving areas.

Perhaps on a related front, the CRTC re-opened its consultation on the Broadband Fund, inviting comments until June 5. The original Notice of Consultation had comments close last September.

These are going to be files worth watching.