As some will recall, prior to becoming a talk show host, Stephen Colbert starred as a right-wing pundit on a satirical news show entitled The Colbert Report. Colbert, the pundit, was billed as America’s most fearless purveyor of “truthiness”. What is truthiness? It’s “the belief or assertion that a particular statement is true based on the intuition or perceptions without regard to evidence, logic, intellectual examination, or facts”.

I was reminded of truthiness when I watched CRTC Chair Ian Scott’s appearance before the February 8 meeting of the House of Commons Standing Committee on Industry and Technology (INDU).

Giving elected officials the chance to ask questions of regulators is an important part of our democratic process. It can be very informative when used wisely. Unfortunately, the opportunity is wasted if Committee members are unprepared or do not have a solid understanding of the industries they are overseeing.

There was a lot of truthiness on display at INDU as Committee members repeated inaccuracies about wholesale internet access rates, the state of competition in the wireless industry, the reasons for the lack of foreign entry, and the role of MVNOs in the wireless market. Some of these topics were discussed in my post last year (“Mythbusting Canadian Telecom”), but these misunderstandings refuse to go away and deserve revisiting.

Myth #1: The CRTC raised wholesale internet access rates

Few regulatory files have been as misunderstood as the setting of wholesale rates for internet service providers (ISPs) dependent on using facilities of carriers that have invested billions in building Canada’s digital infrastructure. These reseller ISPs operate using connections built by wireline carriers, paying wholesale rates that are set by the CRTC.

For as long as I have been around, these rates have been in dispute. Indeed, the interconnection architectures have been subjects of multiple regulatory battles as independent service providers seek alternate ways to arbitrage the connections provided by the facilities-based service providers [see, for example, the CRTC’s wholesale services framework set in July 2015].

The latest rates dispute actually began in May 2015, when the CRTC began a “Review of costing inputs and application process for wholesale high-speed access services.” In early 2016, the CRTC resolved that consultation and made a determination on processes to set the wholesale rates. In October 2016, the CRTC established substantially lower wholesale rates that it designated as “interim” while it undertook a more extensive review. These interim rates reduced the transport component by up to 89%, and the access component rates by up to 39%. Notably, at the time, CNOC issued a statement saying “The CRTC’s actions will immediately benefit both Canadian consumers and businesses and we are hopeful that the final outcome of this matter will have the same result.”

In 2019, the CRTC issued its “final” determination, setting rates that lowered the rates even more, rates that the Commission later acknowledged were based on mistakes. Those 2019 wholesale rates were never given effect; the 2019 decision was immediately made the subject of multiple channels of appeal and the rates were stayed. In May 2021, the CRTC finalized the rates and issued a wholesale broadband service background paper describing the process.

As the CRTC Chair told INDU, “When we analyzed the evidence, we found errors and could no longer justify the associated rates. Ultimately, we chose to reaffirm and make final the interim rates that we set in 2016, with some adjustments.”

Most importantly, as INDU was told, “the 2019 rates were never in effect in the marketplace.”

The CRTC did not raise wholesale internet access rates. It lowered them.

Myth #2: Canada has a lack of competition compared to other countries

Many have heard it said that the Canadian wireless market is less competitive and more concentrated than in other countries. But how many making such statements have bothered to look at the state of competition in other markets?

I decided to do just that.

[Note: The data in Figures 1 through 4 is from Telegeography (September 2021). The source data for Figure 5 is The Economist Intelligence Unit – The Inclusive Internet Index – 2021]

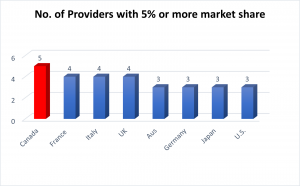

One way to look at competition is by the number of mobile wireless carriers in each market. If you listen to some commentators, you might assume that Canada has fewer carriers than most other countries.

In fact, the opposite is true.

As shown in Figure 1, Canada has more mobile service providers with a 5% market share than any other country in the G7 plus Australia.

Some may respond by saying that despite having five carriers that surpass the 5% threshold, Canada’s three national carriers dominate the market.

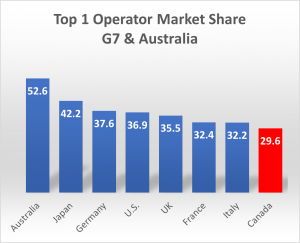

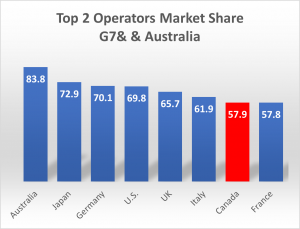

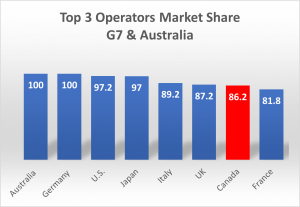

Sure, the national carriers are bigger than the regional providers, but does that make Canada an outlier compared to its peers?

The facts show otherwise.

Figures 2, 3 and 4 illustrate that Canada’s wireless market is less concentrated than peer countries (other than France) when you look at the market share of the leading carrier, the share of the top two carriers, and the top three carriers.

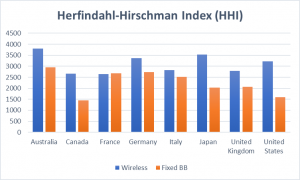

Another commonly accepted measure of market concentration is the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). HHI is calculated by squaring the market share of each competing firm and then summing the result.

An HHI of 10,000 would indicate one company in a market with 100% market share, while a market of thousands of firms, each with less than 1% market share would have an HHI of close to zero. In other words, the lower the HHI, the less concentrated a market is.

Despite these facts, critics of Canada’s wireless industry continue to argue that a lack of competition is the cause of whatever aspect of the market they are rallying against.

Since it isn’t the competitive intensity, perhaps more attention should be paid to other factors that distinguish Canada from other countries.

For example, readers of this page know that I have frequently discussed the high quality and expansive coverage of Canada’s digital infrastructure, despite substantially higher costs associated with spectrum and building networks to serve Canada’s widely-dispersed and smaller population.

Myth #3: More MVNOs would reduce prices in Canada

At INDU, one MP suggested that the CRTC said “no” to Mobile Virtual Network Operators (MVNOs).

No, the CRTC did no such thing.

The Commission refused to mandate MVNOs, but that is the same as virtually every regulatory body around the world. And similar to most jurisdictions, MVNOs are indeed permitted in Canada.

And MVNOs actually exist in the Canadian market. But, implicit in the MP’s questioning was the idea that having more MVNOs would result in lower consumer prices. It’s an appealing argument, until you look at the facts and understand that the objective of MVNOs is not to lower prices, it is to make a profit.

Outside of China, the countries with the largest MVNO market are the US, Germany, and Japan. It is estimated that Japan has about 170 MNVOs. If there were a relationship between the number of MVNOs and lower prices, one would assume that these three countries would also have the lowest wireless prices. They do not. As shown by ISED’s most recent international price comparison report, wireless prices in these countries are similar to, and in some cases higher than, prices in Canada.

So why do these countries have so many MVNOs?

Mobile carriers in these countries decided that part of their business strategy would be to use resellers and other brands to acquire customers for their network services. In some cases, they use a sub-brand that they own; in other cases, they enter into a commercial arrangement with an independent brand. For the independent brand, the motivation is not to lower prices; like all businesses, their objective is to make a profit. Some were successful by targeting specific demographics or brand-aware groups, while many were unsuccessful and have gone out of business. But the bottom line remains: the number of MVNOs does not correlate to lower prices.

Myth #4: Foreign companies are not allowed to offer wireless services in Canada

I continue to be surprised at the persistence of this myth. But even more surprising was to hear a Conservative MP raise the issue at INDU, when almost ten years ago the Conservative-led government removed nearly all restrictions on foreign companies operating in the Canadian wireless market. The only remaining restriction is a foreign-owned company cannot gain entry by acquiring any of the three national carriers.

What is stopping them from launching a competing wireless business in Canada? I can only speculate, but I think it is reasonable to assume that they have looked at the amount of investment required to acquire spectrum and build out a network, the relatively small population of Canada, and, as discussed in Myth 1 above, the number of carriers already in the market, and concluded the business case simply does not work.

It is economics, not regulations, that drives their decision-making.

Why do I continue to address these myths?

I try to tackle these myths for the same reason I write this blog.

You cannot properly oversee a market that you do not understand. Canada and Canadians will not benefit from policies based upon the “truthiness” of feelings and perceptions.

Balancing the policy objectives of quality, network coverage, and affordability requires a deep understanding of the Canadian telecom market, how it compares to other countries, as well as looking at the positive and negative impacts of policy decisions made in other countries to try to avoid unintended consequences.

We can, and must, do better to ensure that the digital networks that helped maintain economic and social activity during the COVID-19 pandemic can propel Canada into a future of economic and social prosperity.

Canada’s future depends on continued investment in connectivity.

Good stuff.

What about data around what capacity we get for our dollar? I seem to recall US carriers offer similar or even higher monthly pricing for wireless service but the amount of data they provide is higher, so the consumer actually gets more bits/dollar. Is this true? I have unlimited Rogers but the access speed reduces after a data limit has been reached (which we as a family have never reached, 80GB).

Your last sentence is key to that calculation: “we as a family have never reached [our data limit]”. In such a case, wouldn’t it be irrelevant that a similar or higher priced offer includes more data to be left unused?

This is a great read. As industry stakeholders, it seems we need to do more to inform and educate our MPs!