Structurally separate doesn’t build better

I’d like to follow up on the passing reference I made recently to structural separation in my post about Australia’s broadband quagmire, the $50B government sinkhole known as NBN.

Structural separation is the regulatory theory that posits better consumer outcomes will be achieved if regulations require a separation between the builders of telecom network infrastructure and the retailers of telecom services. The theory is that the infrastructure company will have incentives to invest all of its energy in building better networks, and the various retail service providers will compete on an equal footing to deliver service excellence.

Two and a half years ago, at a meeting of Parliament’s Industry Committee (INDU), the British model was identified by Canadian Conservative MP Michelle Rempel Garner as an potential example for Canadian telecom policy. Tony Geheran, Chief Operations Officer at TELUS told the Committee, “I haven’t seen that work anywhere globally, to sustainable effect.”

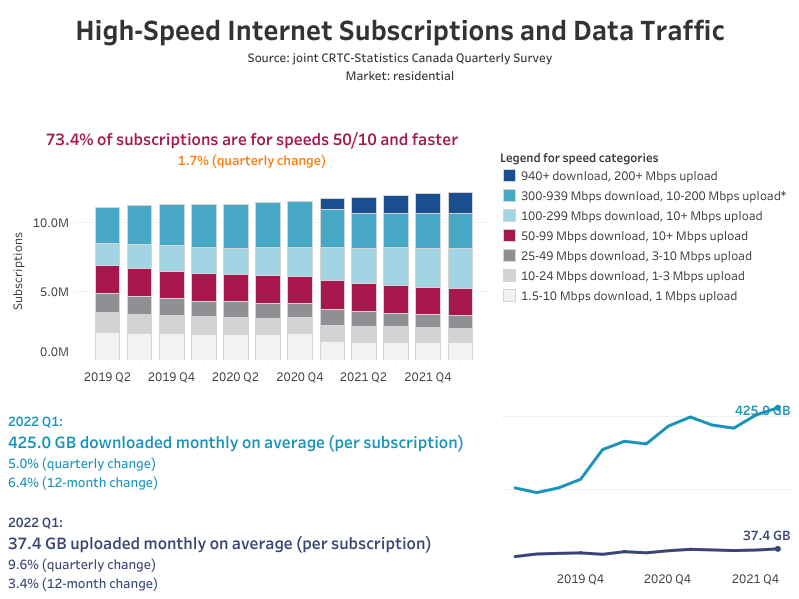

At the time (May 19, 2020), I noted “Ofcom is showing that broadband speeds in the UK increased 18% between 2017 and 2018 to reach 54.2 Mbps. According to the CRTC, average speeds in Canada reached 126.0 Mbps by the end of 2018, an 89% increase over 2017.”

A year later (May 19, 2021), I provided an update: “According to Ofcom, “the average download speed of UK residential broadband services increased by 25% since 2019, from 64 Mbit/s to 80.2 Mbit/s.” According to the CRTC, at year-end 2019, 18 months ago, the average download speed in Canada was already 176.9 Mbps, more than double the current speed in the UK.”

Some recent articles show that the situation hasn’t improved for those in the UK. A recent article in the Financial Times says “almost a hundred smaller alternative networks — or “altnets” — have emerged with the goal of laying fibre as quickly as possible to attract customers frustrated by their existing service”. As it turns out, these “altnets”, such as Virgin Media O2 and the UK’s largest altnet, CityFibre, have argued against BT OpenReach lowering its wholesale prices, claiming the move would be uncompetitive.

The CRTC is reporting Canada’s average download speed was 220.4 Mbps by year end 2020, two and a half times what the UK regulator has observed.

Structural separation isn’t a solution. As Tony Geheren told INDU in May of 2020, “if you look at the UK, they are wholesale moaning about the quality of their infrastructure, their lack of fibre coverage. across what is a very small geography. I know. I originated from there. And quite frankly, the Canadian networks are far superior in coverage and quality and performance through COVID has demonstrated that.”

The Canadian model, creating a policy environment that encourages private sector investment in competitive infrastructures, means that most Canadians can choose from multiple suppliers of broadband access. It is a framework that has delivered better broadband for more Canadians than the structurally separated policies in the UK and (as discussed a few weeks ago) in Australia.