Last week, an article in the Globe and Mail called for a reboot of Canada’s digital agenda.

On that headline point, I agree. A reboot may be needed.

As part of a typical reboot process, systems start fresh with clean data, clearing out faulty information. Some systems apply filters to improve the signal to noise ratios. As part of the reboot process, the government should ensure the information being loaded for processing passes error checks.

Unfortunately, I found a few points in the article that would fail error detection algorithms.

For example, in the second paragraph, we read:

The Liberals identified consumer telecom pricing, privacy protection and a modernized internet legal framework as priorities, but have struggled to develop an effective approach. Navdeep Bains, the Innovation, Science and Industry Minister, surprisingly backed a reversal on the affordability of communications services last month and has done little on privacy reform.

There is a little sleight of hand at work in those two sentences. Although affordability and prices are related, they are not the same and the terms should not have been used interchangeably. Indeed, recall from my post in January that a report from PwC found Canada’s telecom services to be the most affordable of all our G7 partners.

Contrary to the article’s assertion, it isn’t true that Minister Bains “backed a reversal on the affordability of communications services last month.” That simply didn’t happen.

The article is apparently referring to last month’s Order in Council responding to a petition to review the CRTC’s wholesale rates Order of August 2019. Minister Bains explicitly said “Canada’s future depends on connectivity,” and indicated that Cabinet was concerned the CRTC had not balanced the objectives in a manner consistent with the government’s priorities. Minister Bains specifically chose not to act at this time, recognizing that the CRTC was already reviewing its decision. Instead, the Minister more clearly indicated the policy of the government. That is precisely what the government is supposed to be doing.

The government’s telecom policy has never had a single-minded focus on price. As I wrote a couple weeks ago, for years now, Minister Bains has consistently spoken of 3 priorities: Quality, Coverage, and Price. Price is just one element. Last month’s Order in Council should be recognized for helping guide the regulator through the challenges of balancing the policy objectives.

Look at the language of the Order in Council:

- “the Commission… is bound… to exercise its powers and perform its duties with a view to implementing the Canadian telecommunications policy objectives and in accordance with any orders made by the Governor in Council”

- “improved consumer choice and competition, further investment in high-quality networks, innovative service offerings and reasonable prices for consumers”

- “considers that the final rates set by the decision do not, in all instances, appropriately balance the objectives of the wholesale services framework… and that they will, in some instances, undermine investment in high-quality networks.”

The Order in Council sought to clarify the need for maintaining the balance.

Indeed, the Globe article itself acknowledges that “fast internet access is a must for all Canadians”, as we have all seen over the past 6 months of being home-bound. Unfortunately, the reader of the Globe article is left without an understanding of the tension between the objectives of quality, coverage and price.

Around the world, we can see what happens when low prices constrain investment, or what I have called the “high cost of low prices”.

The message from Cabinet was clear.

On the basis of its review, the Governor in Council considers that the rates do not, in all instances, appropriately balance the policy objectives of the wholesale services framework and is concerned that these rates may undermine investment in high-quality networks, particularly in rural and remote areas. Retroactive payments to affected wholesale clients are appropriate in principle and can foster cooperation in regulatory proceedings. However, these payments, which reflect the rates, must be balanced so as not to stifle network investments. Incentives for ongoing investment, particularly to foster enhanced connectivity for those who are unserved or underserved, are a critical objective of the overall policies governing telecommunications, including these wholesale rates.

This should not be viewed as a “reversal on the affordability of communications services.” Instead, as should be evident to most Canadians over the past 6 months, the pandemic has helped elevate awareness in the importance of Quality and Coverage, the other two legs of the Minister’s priorities. The government called for improving the balance to preserve incentives for investment, the key input to ensure Canadians have access to world leading network quality, covering urban and rural areas.

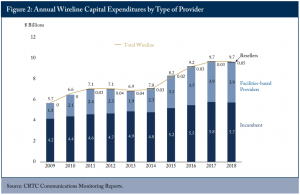

The vast majority of investment in networks – rural and urban, wireless and wireline – the overwhelming majority of capital investment in Canadian networks comes from the private sector, not government. While governments support and supplement network investment by carriers, large and small, governments do not (and generally should not) supplant private sector investment. An approach based on strategic, targeted support helps to ensure a greater reliance on market forces to achieve the objectives of Canada’s telecom policy.

As Cabinet understands, in many cases support for private sector investment does not require cash as much as it requires a policy environment that encourages investment. Cabinet more clearly understands the economics the drive network investment, as I discussed a few weeks ago in “The economics of broadband expansion”.

The Globe article also seems to be confused between judicial appeals and cabinet appeals of regulatory decisions. The article says “the government’s approach seems particularly troubling given that the Federal Court of Appeal last week upheld the CRTC decision.” In reality, this should not be troubling at all; there is no linkage between the two appeals.

In fact, the ruling of the Federal Court of Appeal itself answers the concerns that the article finds “troubling”. As stated by the Court at paragraph 23:

[23] Significantly, neither section 62 nor subsection 12(1) circumscribe the types of questions that may be raised before the CRTC or the Governor in Council. This stands in contradistinction to the prescription in subsection 64(1) that limits this Court to reviewing questions of law or jurisdiction.

The Court is limited to ruling only on “questions of law or jurisdiction” while there are no limits on the scope of issues that may be raised in appeals to Cabinet (the “Governor in Council”) or the CRTC. So, it is completely consistent for a Court to find no fault with questions of law or jurisdiction, but have Cabinet to take issue with a CRTC decision on the basis of matters of policy.

There are valid concerns raised about delays in launching new broadband funding programs and we have unfortunately squandered 3 months of prime broadband construction season in failing to implement what I described as “An easy way to increase rural broadband speeds”.

Looking forward, we need serious discussions on the role of government in implementing the recommendations of the Broadcast and Telecom Legislative Review and updates to other areas impacting the digital economy.

But we need to make sure that when the government does its reboot, it carefully examines the data being input for processing. Much of it needs error-checking.