Feeding at the funding trough

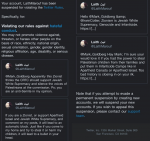

The story of the government engaging an anti-racism consultant with a history of “disturbing comments” has been chronicled here for more than a year (see: July 2021: Funding Hate; April 2022: Purveying hate on the public dime; and, Government funded hate speech). Thanks to amplification from Jonathan Kay’s twitter feed, the story has made its way into the mainstream media, leading (at last) to a government response.

As I wrote last week, the government (and even some opposition members) knew about the problem much earlier, but did not act until the matter became a more public priority. The reasons for this inaction can be the subject of further investigation by the Parliamentary Heritage Committee, or others.

While the focus these past couple weeks has been on the Anti-racism Action Program funding, some may want to explore the ease by which “public interest” groups, such as the one under the microscope, can feed at various troughs of cash in Ottawa.

I raised questions in July of 2021 about a CRTC award of $16,815.10 to CMAC in May of that year. The CRTC awarded an additional $15,332.48 a few months later (October 2021), paring back CMAC’s original request by $2000 “in order to be considered reasonable and necessarily incurred”. In each case, all but $2069.55 (paid to another CMAC consultant) was claimed by Laith Marouf.

In addition, the Broadcast Participation Fund (BPF) represents a pot of cash available to groups since its establishment by the CRTC in 2012. According to the CRTC, the mandate of the BPF is:

- provide costs support to public interest groups and consumer groups representing non-commercial user interests and the public interest before the CRTC in broadcasting matters under the Broadcasting Act;

- support research, analysis and advocacy in both official languages directly related to ongoing CRTC broadcasting proceedings under the Broadcasting Act;

- retain an independent costing officer who shall be responsible for the day-to-day operations of the BPF subject to the overriding authority of the Board; and

- do all things which are in furtherance of the foregoing.

The BPF hands out a lot of cash to public interest groups, totalling just under $900,000 in 2021 alone. Of that total, CMAC received $144,480.44 or more than 15% of the 2021 allocations. There was another $57K granted in 2020; $89K in 2019; $41K in 2018; $88K in 2017; and, $98K in 2016.

That is more than half a million dollars to CMAC over the last 6 years, just from one Ottawa-based fund doling out your money.

The same groups show up on the lists year after year, similar to names of organizations receiving cost awards directly from the CRTC in telecom proceedings.

Who qualifies for funding?

In Telecom and Broadcasting Notice of Consultation 2020-124-2, the Commission stated the following:

15. […] Eligibility for a share of these funds will be evaluated according to the criteria set out in section 68 of the Rules of Procedure, namely

- whether the applicant had, or was the representative of a group or a class of subscribers that had, an interest in the outcome of the proceeding;

- the extent to which the applicant assisted the Commission in developing a better understanding of the matters that were considered; and

- whether the applicant participated in the proceeding in a responsible way.

Should the third criteria, “participating in a responsible way”, include an examination of the character and behaviour of the people involved in the applicant? Is the credibility of the applicant impacted by their character and does that impact the ability to participate in a responsible way?

To whom do these public interest groups answer? Who do these groups actually represent? What due diligence is performed by the guardians of the public funds?

As I highlighted last year, in one set of cost awards, the CRTC didn’t even allow people to provide comments about the cost applications, comments that might have helped inform the Commission of concerns about the recipients of these funds; “the Commission considered that such responses were unnecessary.”

It turns out, that was a bad call.

These various programs and funds have been established with the best of intentions. Unfortunately, there are often unintended consequences that arise from opportunities to access “other people’s money”.

Are the people distributing public funds exercising sufficient checks before disbursing money from these troughs of cash?