In one of my posts last week, I mentioned “Measuring Digital Literacy Gaps Is the First Step to Closing Them“, a recent article from ITIF.

We all agree on the importance of being digitally literate in today’s world. Most of us can’t imagine communicating, working, studying, being entertained, banking, shopping, or driving without using a computer, our smartphone or a tablet. Knowing how to safely use digital devices and the internet is a basic need. However, as ITIF writes “we have no clear system of measuring this type of literacy rate.”

How do we know where our population stands? How do we compare to other comparable countries? Do we have any idea if we have a problem with digital training?

I, for one, suspect we do.

ITIF suggests a data-driven approach, meaning we need to develop measurements for rates of digital literacy.

Simply connecting to the Internet is no longer enough. To really benefit from the information age, populations need the ability to navigate the Internet and use connected devices with some baseline level of skills. To equip our population with essential twenty-first-century skills, we need to standardize that baseline and figure out how to assess whether and when it’s met.

Recall, a few months ago I wrote about Alberta’s approach to upgrading digital skills. Alberta offers two streams, beginner and intermediate. But how do you know which one to take? How do we know the size of our literacy gap in the absence of a measurement tool.

The term digital literacy can mean different things to different people. ITIF cites a definition by the National Digital Inclusion Alliance. “Digital Literacy is the ability to use information and communication technologies to find, evaluate, create, and communicate information, requiring both cognitive and technical skills.” Can you access information online? Do you know how to communicate using email or messenger applications? Are you comfortable with online banking? Joining a Zoom meet-up or webinar?

ITIF notes that since it can be important to identify reasons behind digital illiteracy. For example, does the user have difficulty with problem-solving in general or is it due to unfamiliarity or discomfort with a particular application. These would require different approaches to remediation. “From that perspective, a largely outcome-based definition leaves room for ambiguity.”

Researchers also need to contend with the fact that digital skills themselves, no matter how narrowly defined, can be difficult to measure. Any attempt to measure practical, and not always outwardly discernible skills—such as comfort with or understanding of a particular process—often relies on self-assessment or otherwise self-reported data. This fact opens digital literacy studies up to a measurement problem. Different people’s evaluations of their own competency at the same task might reflect different understandings of what the standards for that competency should be. In other words, people don’t always know what they don’t know.

What gets measured, gets done.

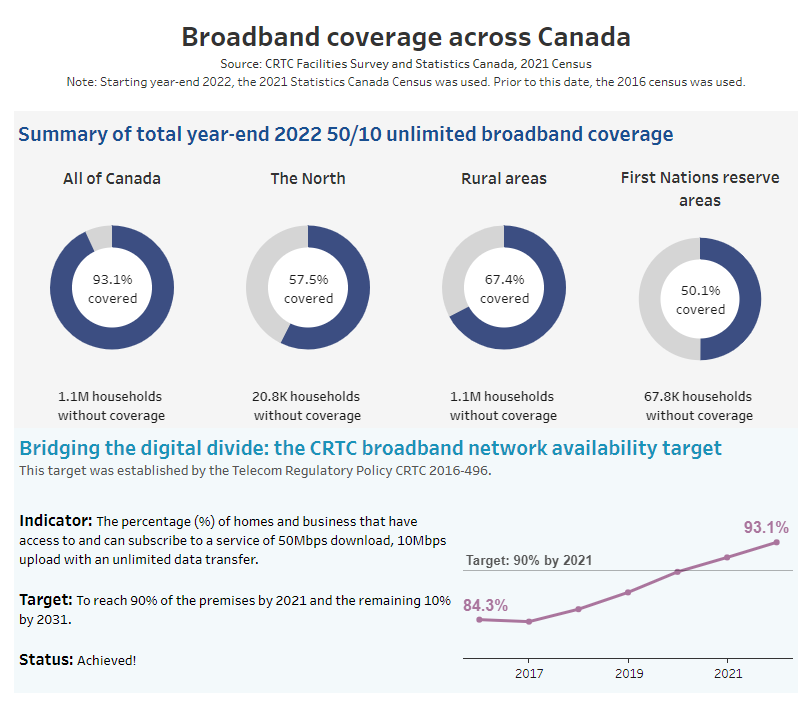

The CRTC and ISED measure progress toward universal access to broadband. But, we also need to focus on the demand side, ensuring Canadians are getting online. It isn’t enough to have access to high speed internet at your doorstep. We need Canadians to actually get online, and feel comfortable doing so.

Should we add digital literacy indicators to Canada’s online dashboard?