If I was asked to put together a list of places in Canada that needed government support for broadband infrastructure, I don’t think the City of Toronto would crack the top 1000 places. I might examine some of the suburbs in the Greater Toronto Area, to make sure those rural areas had upgraded access, but the city proper? Not a chance.

Next week, Toronto’s Executive Committee is considering an item entitled “Affordable Internet Connectivity for All – ConnectTO”. The City’s Technology Services group “is seeking City Council’s support to lead “ConnectTO”, a collaborative program that aims to centralize stewardship of municipal resources and assets to deliver the City’s goals on equity and connectivity, including creation of a City of Toronto broadband network.” A City of Toronto fibre-enabled broadband network is envisioned.

Of course, I am one hundred percent behind initiatives promoting universal affordable internet connectivity. I have been beating that drum for 13 years now, on these pages and in public discussions.

Where I tend to have problems with otherwise well intentioned proposals is in two areas: confusing access to broadband with adoption of broadband services, and confusing affordability with average prices. The 9-part report does both, and in doing so, steers City Council toward a solution for a non-existent technology problem when the focus should be on social services.

The report going to Toronto’s Executive Committee has a number of flaws. In the Report for Action by the City’s Chief Technology Officer, Technology Services Division, the Background reads:

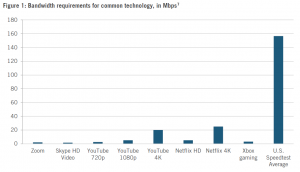

Well-developed broadband infrastructure is essential for residents to participate in the digital economy, learn online, and to access government services. The CRTC has set minimum service levels of at least 50 megabits per second (Mbps) download speed and 10 Mbps upload speed and access to unlimited data for high-speed broadband. However, research from late 2020 indicates that 39% of Torontonians surveyed did not have internet speeds that met the CRTC minimum service level. The same research indicates a majority of the 62 countries in one study offer 100 Mbps as the most frequent internet speed. More recently, there are concerns that 50 Mbps download speed and 10 Mbps upload speed is not sufficient for the more data intensive ways which Canadians are now using the internet, such as online learning, electronic business transactions, etc., especially with multiple simultaneous devices being used in the same household.

I could devote this entire blog post to explain the flaws in this one paragraph.

Many may think, “Who cares? This is just a Background paragraph. Move on.” I think that these flaws form a basis for erroneous thought that tends to permeate through the report and its 8 associated appendices. Some of the materials are wholly irrelevant, as if to provide filler, or add heft to the filed materials. But the recommendations in the report seem to flow from the erroneous background, and that makes me somewhat distrustful of the rest of the materials.

Let’s take a look at some of the problems in this paragraph. I won’t quibble with the first sentence, although it leaves out what most of us use our broadband for: entertainment (music, streaming videos, social media, etc.). But since this is a serious matter before the City executives, I guess the CTO wanted to stick to the introduction lifted verbatim from the CRTC. Unfortunately, that didn’t continue into the second sentence. The CRTC continued with “That is why we set new targets for Internet speeds. We want all Canadian homes and businesses to have access to broadband Internet speeds of at least 50 Mbps for downloads and 10 Mbps for uploads.”

There is a subtle, but important difference there. The CRTC didn’t set a minimum service level. It set a target for all Canadians to be able to access those service characteristics, leaving it up to Canadians to choose whether or not they want to subscribe to that speed. The error in the second sentence is why the very next sentence is so completely misleading and flawed: “However, research from late 2020 indicates that 39% of Torontonians surveyed did not have internet speeds that met the CRTC minimum service level.”

On first read, one might think that Toronto is a broadband backwater, with nearly 40% of of the city unable to access to the CRTC’s broadband speed objectives. That simply isn’t true. Virtually every household in Toronto has access to gigabit speeds (and faster), from at least 2 competing service providers, Bell and Rogers. Many residents have access to alternative fibre-based services from companies like Beanfield Metroconnect.

An appended report from Ryerson, the research source for the data in the above highlighted paragraph, is disappointing in what I see as a lack of scientific and analytic rigour. Much of the report is based on survey data, with 80% of the 2500 responses coming from an online survey. No wonder the study found 98% of the respondents had internet access! The first 80% needed internet access just to answer the survey. The other 2% must have come from the telephone survey respondents.

The Ryerson report, Mapping Toronto’s Digital Divide, contains a number of other data mismatches that can be detected by looking carefully. I’ll highlight a couple instances, such as this paragraph:

A majority of the 62 countries in one study offer 100 Mbps as the most frequent internet speed. Such speeds allow for simultaneous and noninterruptive web browsing on multiple devices, including streaming services in 4K high resolution. While many countries around the world do not offer speeds lower than 100 Mbps, Canada continues to remain among the few internationally to continue to provide internet speeds less than 9 Mbps, alongside notably the US and UK.

Without looking to the footnotes, one might think that the statement in the second sentence refers to the same collection of 62 countries as discussed in the first sentence. But that would be wrong. In fact, the second sentence is based on ISED’s 7 country pricing comparison. The sentence is inaccurate.

Ryerson looked at data speeds as well and the report presents results in an embarrassing and extremely misleading fashion.

The global average download speed for broadband internet as of November 2020 according to one source was 91 Mbps; while the Canadian Internet Registration Authority found the average Ontario download speed was 52 Mbps from April 2019 to March 2020.

There are multiple obvious flaws in this data. The timeframe used for the global datapoint was November, 2020, while the Ontario data is from a year earlier. In addition, the global datapoint came from Ookla’s Speedtest, while the Ontario data is from the deeply flawed CIRA speed test. There was no reason for this. Ookla’s Speedtest has Canadian specific data (156 Mbps), broken down by province (Ontario was 153 Mbps) and indeed, Toronto specific data (171 Mbps). Why wouldn’t the authors match the data source and timeframe?

It comes across as authors torquing the presentation of data to fit some kind of an agenda. Ryerson should retract the report and redo it with greater academic rigour.

Toronto does not have a problem with the availability of broadband, and there is absolutely no reason for the city to contemplate construction of fibre facilities. A number of the appendices are dedicated to maps and analysis of how to build fibre to libraries that clearly have available existing commercial services. If Toronto wants to assist with private sector digital infrastructure investment, it can facilitate access to ducts, rights of way, municipal electric poles or other support structures for fibre, and make available vertical real estate for radio antennas.

I have often written that people frequently confuse broadband adoption with broadband access. It is somewhat easier to contemplate ways to fix gaps in broadband access; it’s just an engineering problem. In urban markets, the economics have permitted multiple competing companies to build gigabit broadband infrastructure to virtually every corner of the city.

It’s a lot tougher to drive adoption. Most telecom companies separate the engineering and operations groups from the marketing and sales groups for a really good reason: these are different disciplines. One side builds and operates the network; marketing and sales develop the services that drive adoption, using the network.

While the Report for Action for the Executive Committee has lengthy discussions about broadband pricing and international comparisons, targeted subsidy programs, such as the nearly 7 year old Connected for Success program from Rogers and TELUS’ Internet for Good get only a passing mention in the Ryerson appendix, not the main document. Considering the history of Connected for Success, launched originally with Toronto Community Housing before being taken across the Rogers network, it might have deserved more significant consideration by the proponents.

Toronto, and indeed every city, has a broadband adoption challenge among certain disadvantaged sectors. As the ConnectTO agenda item Summary indicates, “access to high-speed internet is necessary for residents to equitably participate in day to day life.”

But, my concern is that this proposal veered off course with its line: “Technology Services is seeking City Council’s support to lead ‘ConnectTO'”. In November 2017, in a memo to the Economic Development Committee, Toronto’s CIO and GM of Economic Development and Culture wrote, “In Toronto nearly 100% of households have ‘access’ but this refers only to the necessary infrastructure being in place. In practice, access depends on affordability.” It is disheartening that so little progress has been made in more than three years.

This isn’t a technology issue. It requires marketing and product development. The lead should be with the agencies invested in delivering community services to disadvantaged members of the community.