Regulatory certainty drives investment

Bell Canada is crediting regulatory certainty and a positive investment climate in announcing an accelerated capital investment program. In February 2021, Bell had announced plans for $1B to $1.2B in additional network funding to help drive Canada’s recovery from the COVID crisis.

According to the press release, with last week’s CRTC decision and “ongoing government policy support for facilities-based competition and investment, Bell has now increased the amount of accelerated funding to $1.5 billion to $1.7 billion.”

The CRTC reinforced its long-standing support for facilities-based competition in the opening paragraphs of the decision:

The Commission’s general approach towards wholesale service regulation has been to promote facilities-based competition wherever possible. Facilities-based competition, in which competitors primarily use their own telecommunications facilities and networks to compete instead of leasing them from other carriers, is typically regarded as the most sustainable form of competition.

Its accompanying press release talked about the plan to migrate to a disaggregated wholesale interconnection model to “increase competition and investments”. These were important signals to the capital markets and companies that invest in facilities.

Last summer, in “The economics of broadband expansion” I described how wholesale rates impact the business case for rural broadband expansion. The announcement from Bell is the first evidence of the spin-off consumer benefits to emerge from the decision.

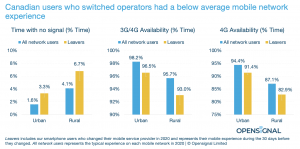

The consumer interest is much more than just price. As I wrote last week, we know that consumers value network quality and will switch service providers in order to get a better network experience.

It is why regulators have to balance a variety of public interest issues in its deliberations, such as investment in broadband; expanding access to unserved areas; upgrades to existing areas with faster speeds and newer technologies and capabilities. In “Acting in the public interest” I talk about the tension in balancing quality, coverage and price, the priorities described a number of times by former ISED Minister Navdeep Bains.

In a six-part Twitter thread, I pointed out the importance of looking at complex regulatory and policy issues from a more holistic vantage point.

Thread about the need to look at 'consumer interest' as more than just a matter of price

We see evidence consumers value service quality, better coverage https://t.co/vV9Af6BHv3

Issues are more complex than a slogan or hashtag#CRTC @ISED_CA @FP_Champagne #CDNtech #CDNpoli

1/6— Mark Goldberg (@Mark_Goldberg) May 31, 2021

“Canada’s future depends on connectivity”. Connectivity requires investment to expand coverage and improve quality. Billions of dollars of investment.

From Bell’s announcement: “Now, with greater regulatory stability fostering an improved investment climate, Bell is proud to take our plan even further by growing our investment to advance how Canadians in communities large and small connect with each other and the world.”

Satisfying the consumer interest is a broader issue than simply lowering prices. The CRTC’s affirmation of its support for facilities-based competition supports the investment necessary for improving quality and coverage as well.