Need to look beyond price

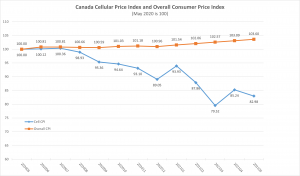

Consumer Reports released a survey [pdf, 600KB] earlier this week that seems to confirm something that I have been saying for a while – that the price of broadband isn’t what is keeping most Americans from subscribing. Consumer Reports found the median price paid for broadband in the US is US$70 (about C$88).

When asking Americans who don’t have broadband why they don’t subscribe, just 32% said it costs too much, less than a third of respondents. A quarter said it wasn’t available and one in six said “they just don’t want it.”

There is no question that Canada, as a country, needs to do more to address the issue of broadband affordability for low income households. The United States has a number of programs that provide a direct benefit to help cover the cost of broadband service for disadvantaged Americans, including the FCC’s US$50/month Emergency Broadband Benefit. The bipartisan infrastructure bill includes an additional US$14B for broadband affordability vouchers.

No such program exists in Canada. Across Canada, special pricing for broadband services targeted at low-income households is completely funded by the service providers themselves, without government funding.

But, as Consumer Reports has found, and as I described in “The broadband divide’s little secret”, we need to look beyond price if we want to achieve universal adoption of broadband.

We need to understand the factors that lead some people to say “they just don’t want it” and overcome these issues.

At the end of the day, it comes back to this point: building universal broadband connections is a relatively easy job; it just needs money. Driving universal broadband adoption is a lot harder. Building better broadband just isn’t enough.

We need policy makers to start turning their minds to the harder task at hand.