Canada needs to be a global leader in 5G

Canada needs to be a global leader in 5G.

That simple statement could, and perhaps should be the focus for Minister Champagne’s digital connectivity strategy.

Every funding program, spectrum allocation, infrastructure policy, should be structured toward achievement of that objective. Easy to remember, it makes a good soundbite: Canada needs to be a global leader in 5G. What is your strategy? Canada needs to be a global leader in 5G.

However, “Market forces alone will not deliver fast 5G internet to rural areas.” That statement, an extension of a foundational truth that has underpinned government broadband incentive programs for two decades, was the title of a recent article on Policy Options. “Canada must adopt measures that ensure universal, high-quality internet access and encourage early adoption of emerging 5G wireless technologies.”

No argument from me. Current rollouts of 5G promise to have service available to at least 70% of Canada’s population by year end.

Now, the authors claim Canada’s current broadband objective, that every Canadian should have the option to subscribe to a 50 Mbps (down) / 10 Mbps (up) with an unlimited data option, is already obsolete, due to the availability of much higher speeds in urban areas. I think this assertion needs further discussion. “The objective would be to give virtually every person access to essentially the same quality of internet connectivity, whether they reside in a major city or a remote Indigenous community.” While this may be a noble objective, it strikes me as somewhat naive. Indeed, the authors themselves acknowledge that.

FTTH may not be feasible for roughly 5 per cent of households – about 700,000 to 800,000 homes. Therefore, future-proofing the hardest to reach populations will depend on a combination of fixed wireless access (using 5G technology) and the emerging generation of globe-spanning low-earth-orbit (LEO) satellites, such as Telesat’s Lightspeed and SpaceX’s Starlink, to provide access where FTTH is not possible.

So let’s not get hung up on the specifics of what technology delivers “essentially the same quality of internet connectivity.” I tend to subscribe to the view that there are compromises necessitated by geographic considerations that preclude equivalent connectivity in remote areas compared to the services available in major centres. However, as Jagger and Richards wrote,

You can’t always get what you want

But if you try sometimes, well, you just might find

You get what you need.

Fixed wireless and low-earth-orbit satellites are great technologies, providing broadband connectivity that meets and exceeds the current aspirational objective set by the CRTC and the government for universal access. The services offered by these technologies meet and exceed the needs of most Canadians.

The Policy Options article expands on a Public Policy Forum discussion (and paper [pdf, 1.8 MB]), “Future Proof: Connecting Post-Pandemic Canada”, that contains two recommendations:

- Canada commit to universal provision of future-proof digital connectivity infrastructure—connectivity that is scalable, so it can support data rates that far exceed the needs that can be foreseen today.

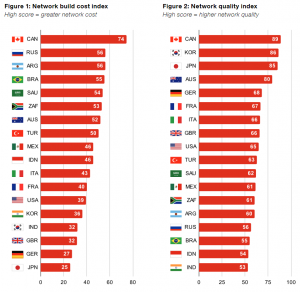

- Canada implement a national strategy to be among the global leaders in 5G with action by government to remove roadblocks on both the supply and demand sides.

While I might quibble over the phrasing of the first recommendation, I can fully endorse the second.

The paper says there are three areas for focus to encourage leadership in 5G connectivity: Network rollout; Spectrum allocation; and, Access to structures (poles, buildings, and trenches) and passive infrastructure.

Universal access to fibre to the home simply isn’t possible in a country as vast as Canada, with harsh winters that regularly disrupt aerial cables and topography like the granite of the Canadian Shield that makes buried cabling oppressively expensive. However, the paper suggests we use 5G technology connected by fibre and LEO umbilicals.

There is a powerful synergy between 5G provision and future-proof Internet access. This is because the extension throughout the country of fibre and LEO constellations such as Telesat’s provides the backhaul capacity needed by 5G networks, while 5Gpowered fixed wireless can provide future-proof Internet connectivity in many places where fibre cannot reach. The functionality of wired and wireless connectivity is converging, with 5G as a major step towards providing the equivalent of fibre through the air.

There are strong comments in the paper, not so subtly calling for significant changes to Canada’s spectrum policy.

Canada should allocate spectrum for 5G more nearly in step with the U.S. than is currently the case. In addition, the design of the 5G spectrum allocation process must take into account requirements to make the best use of 5G technology—e.g. by providing contiguous blocks of spectrum to support the highest speed. Spectrum policy should balance the objective to promote competition with the need to maintain the incentive to invest in new technology for which market returns are uncertain at the outset.

To be a global leader in 5G, Canada needs to develop such a strategy, and then must take the steps to implement that strategy across all agencies. “Set clear objectives. Align activities with the achievement of those objectives. Stop doing things that are contrary to the objectives.”

And that brings us back to the question: Will Minister Champagne make 5G leadership a central theme of his approach to digital connectivity?