The thrill of victory. The agony of defeat.

The government should be celebrating “the thrill of victory.”

Last summer, I wrote how it was time for government policy makers to declare “Mission Accomplished”. Price reductions in the mobile market were “well beyond any of the expectations that were set by Ottawa”.

While such a mission accomplished statement was likely too much to ask for, the Government’s virtual silence surrounding the significant declines in wireless service prices is counterproductive and somewhat perplexing.

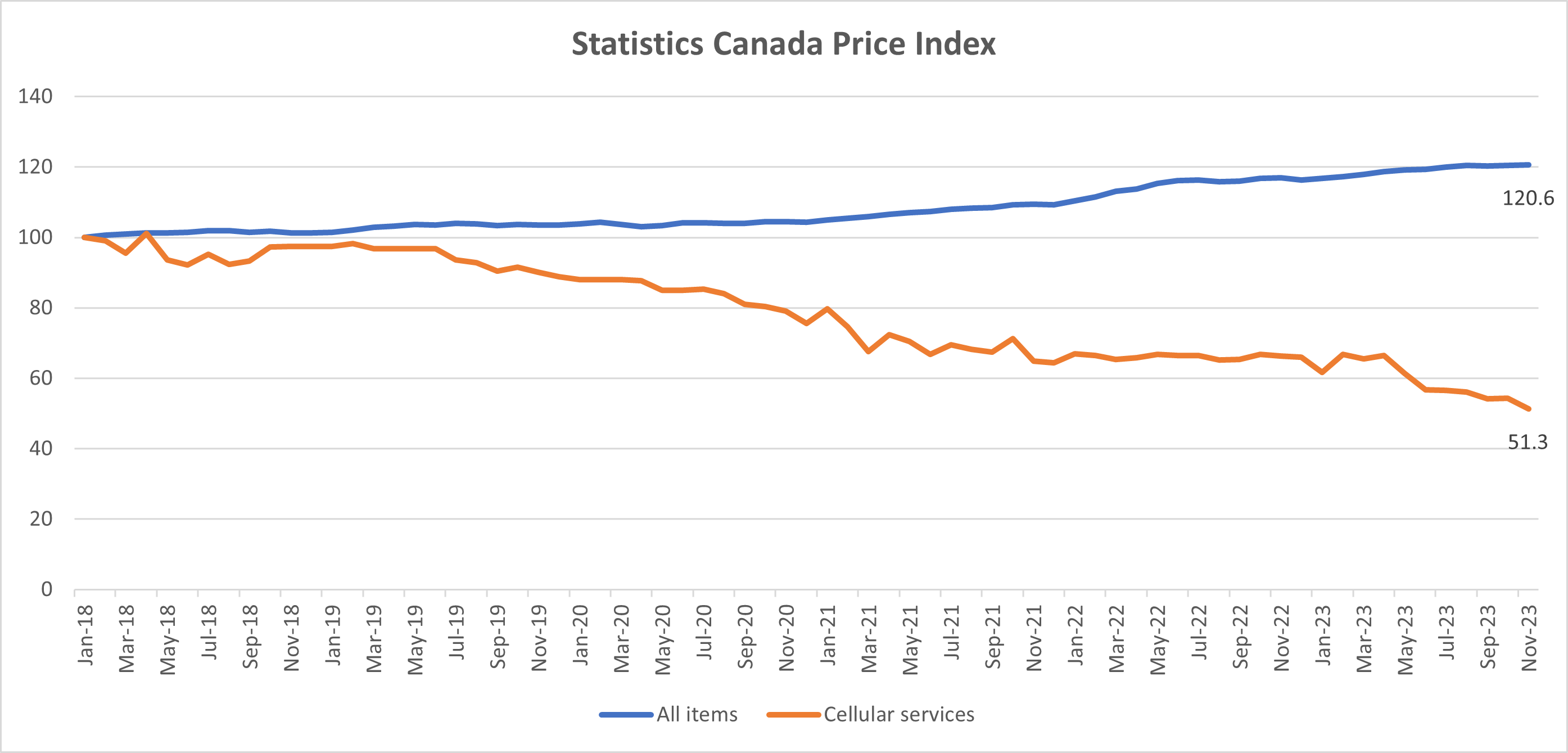

Statistics Canada’s Cellular Price Index has declined by 22% in the last year and by almost 50% since 2018. While impressive, it is even more remarkable given that inflation has driven overall prices up by more than 20% since 2018.

So, when opposition parties repeatedly claim that the government has done nothing to lower prices and has failed to keep its 25% price reduction, one might think the Government would have an easy time refuting such claims. One might have even expected Minister Champagne to point out that prices for wireless services are lower than they have ever been, all under this Government’s tenure. That old “Promise made; promise kept” thing.

But, that isn’t what is happening. Having made the telecom industry its political punching bag, the Government has shown itself incapable of pulling its punches. If anything, the Government appears to regard as a weakness any kind of acknowledgment that the industry succeeded in making services more affordable for Canadians.

The failure to properly acknowledge the decline in Canadian mobile prices is a form of misinformation, perpetuating a distorted view of the industry. This leads to uninformed public discourse, and misguided policy and regulation.

In doing so, the Government has ceded the narrative to the opposition parties, who are continuing to push outdated facts and perceptions. As a result, the government comes across as being on the defensive, giving Canadians the impression that they have nothing to show for their years in office.

Let’s look at the accusation that the government has failed to meet its 25% price reduction objective.

As you may recall, in 2020 the government set an expectation that the national carriers would reduce the price of 2GB, 4Gb, and 6GB, so-called mid-range, plans by 25% within two years. As the chart below illustrates, this objective was achieved prior to the two-year deadline. Two years ago, the government boasted that the reductions “were achieved across the country three months before the target date.”

| Data in Plan | Benchmark | Price as of March 2022 | Change in price (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 GB | $50.00 | $37.50 | -25% |

| 4 GB | $55.00 | $41.25 | -25% |

| 6 GB | $60.00 | $45.00 | -25% |

But, the good news does not stop there. As a result of vigorous competition in the mobile services marketplace, those March 2022 target price points come with substantially more data.

The government’s objective was for Canadians to get a 4G plan for $37.50 with 2GB of data. Yet, a quick survey of carrier websites shows that today there are plans from various carriers for $37.50 (or lower) offering 30GB to 50GB, including some that include 5G speeds. That represents up to a 96% reduction in the price per GB compared to the March 2022 target. This does not include some expired Boxing Day promotions that offered even more data.

The $45 price point has a similar result:

| Price Point | March 2022 Data Bucket | January 2024 Data Bucket | Change in $ / GB |

|---|---|---|---|

| $37.50 | 2 GB (4G plans only) | 30 to 50 GB (4G and 5G plans) | Up to -96% |

| $45.00 | 4 to 6 GB (4G plans only) | 50 to 75 GB (4G and 5G plans | Up to -95% (compared to 4 GB) Up to -92% (compared to 6 GB) |

Let’s be really clear. The promise of a 25% reduction in mobile prices promise was not only met, but carriers have exceeded the government’s expectations – by far.

But, you’d probably only know that by reading it here.

We will soon be entering a federal election cycle. The current government will have to defend its record on a host of issues, including telecom policy.

By perpetuating outdated and unfounded perceptions that Canadians pay “too much” for wireless services, the Government is painting its policy initiatives (and election promises) as failures, even though the facts say otherwise. When the previous government was in office, it cost over $80 for a plan with 2GB of mobile data. Today Canadians can get as much as 75GB for $45. This should be a good news story – the thrill of victory.

By failing to highlight these obvious truths, the government is snatching defeat from the jaws of victory. And, it is suffering the resultant agony.

Which of my blog posts were the Top 5 in 2023, the ones that attracted the most attention?

Which of my blog posts were the Top 5 in 2023, the ones that attracted the most attention?