Mobile prices have fallen more than 25% over the past year, according to Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada’s “2019 Price Comparisons of Wireline, Wireless and Internet Services in Canada and with Foreign Jurisdictions” [pdf, 2.1MB], the 12th annual edition of the report.

The report is dated November 7, 2019, which means the work product has been sitting around for 4 months, waiting for today’s disclosure. The information gathered in the main body of the report was known to be stale even before it was completed. The study gathered its main pricing information in May 2019, a month before what the report calls “the relatively recent introduction of significantly modified mobile plans … Some of the market changes are greater standardization of national MNO pricing across the country as well as the offering of higher end data caps at reduced prices.” That statement appears to contradict observations that prices are lower in provinces with ‘strong regional competitors’, in evidence presented by the Competition Bureau at the CRTC’s Wireless Review.

The prices changed substantially, the plan structures changed substantially, and prices were seen to be more consistent across the country. But, rather than redo the study in its entirety, all that was done was add a ‘spotlight’ section to provide highlights of the impact of the updated rates. Moreover, according to the study authors, “foreign jurisdiction price data was primarily collected in June/July 2019”, meaning the study authors were still in the process of collecting data when the new Canadian rate plans were in the market.

Policy statements are being made based on outdated data. Regulatory measures are being contemplated based on detailed data collection that was stale before the report was written. In 2018, Canadian mobile services revenues were more than $27B. How much would it have cost to get the data right by updating the Canadian pricing data? This fundamental error in judgment is especially troubling since the already outdated report sat unreleased on a desk for a further 4 months. [Note: alleged flaws in the methodology used in the annual pricing study are described in detail in evidence filed by NERA in the CRTC’s Review of Mobile Services.]

Earlier this week, I wrote about the much more sophisticated pricing study conducted for the CTIA that used regression analysis that “considers differences in plan characteristics, network qualities, and country attributes, allowing the authors to compare value propositions, and not just a superficial price comparison.”

The CTIA study looked at the ISED methodology and observed that its comparisons are based on “six artificial demand baskets”. “Moreover, depending on how similar or dissimilar the plans are in each basket, the study reports drastic and incredible price fluctuations from year to year.” In the view of the authors of the CTIA study, “Because the baskets lack an empirical foundation, this results in a price comparison of drastically different plans that produces meaningless results.”

Extreme caution should be exercised in interpreting the data in this year’s report released by ISED. A few years ago, the study acknowledged its limitations.

Despite the current report missing the important “caveats” section acknowledging the study limitations, let’s take a closer look and carefully consider the cautions that were disclosed in the 2016 edition of the study.

- “The price comparisons are based on price data collected through a survey conducted in January and February of this year. As prices for telecommunications services are constantly evolving, the prices cited in this Study represent a ‘snapshot’ of prices in time. Also, the price differentials found are highly sensitive to currency fluctuations.”

Any study is naturally a snapshot in time. We know that the market is dynamic by virtue of regular articles like Mobile Syrup’s “Here are the changes to Canadian carrier rate plans this week”. Multiply those changes by the other countries in the study and add in currency fluctuations and you have a significant challenge.

- “Thus, the prices cited for Canada, US or the international jurisdictions are not meant to be statistically representative of the individual countries as a whole.”

Will this limitation be considered in the reporting on this study?

- “Prices in Canada and international jurisdictions are driven by a complex mix of a number of factors: cost of service, competitive positioning, technological advances, consumer behaviour and regulatory frameworks.”

The study conducted for CTIA was designed to account for many of these variables that are key to the value proposition placed in front of consumers. It found Canada beat the countries used by ISED when accounting for such factors.

- “As wireless technology is constantly improving and consumers demand ever more bandwidth and data caps, service providers are constantly increasing features. In the Study, these changes are reflected by the need to regularly update the definition of service baskets. Hence, price increases in those baskets may in part, simply reflect better service levels offered to consumers.” [emphasis added]

Will this limitation be considered in the reporting on this year’s study?

- “This Study did not take into account the network technologies deployed in the networks nor the speed or quality of service of those networks. Finally, this Study did not account for any cost of service or socio-economic factors that may be relevant for price differences across different domestic and international jurisdictions.”

The study conducted for CTIA was designed to account for many of these variables that are key to the value proposition placed in front of consumers. It found Canada beat the countries used by ISED when accounting for such factors.

- “factors such as population density, terrain and climate have significant impacts on the cost of service.”

The study conducted for CTIA was designed to account for many of these variables that are key to the value proposition placed in front of consumers. It found Canada beat the countries used by ISED when accounting for such factors.

- “socio-economic factors such as affordability indicators (i.e. mobile prices in relation to disposable income), number of handsets per subscriber, number of minutes of usage per subscriber and other factors were not within the scope of this Study.”

Last month, I reported on an independent study on mobile service affordability, with PwC’s examination of the claim that “household budgets were being strained by spending on mobile plans”. Other attributes associated with the consumer value proposition are accounted for in the CTIA study methodology.

There are limitations to any study, and in 2016, the study conducted for the Canadian government carefully cautioned readers on the kinds of interpretations and conclusions that can be drawn from it.

Why has this section that highlights limitations of the study disappeared?

Watch for reporting on the study. Just because the report doesn’t contain a ‘caveats’ section doesn’t mean the limitations have gone away. The international price comparisons are completely meaningless in this year’s report given the significant price changes that took place in Canada.

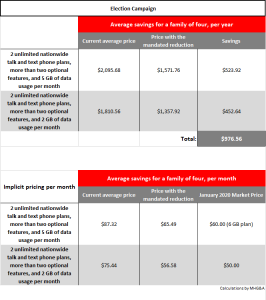

The government plans to monitor and report on mobile plan pricing on a quarterly basis for 2GB, 4GB and 6GB plans. The spotlight section of today’s report shows the price of 2GB plans fell 30% between May and September; 5 GB plans fell almost 25% in the same period. Earlier this week, a US-based study conducted for the CTIA (based on current mobile industry pricing) “puts Canada atop the G7 + Australia when considering the price-value relationship in mobile wireless services.” In December, PwC found Canadian mobile services topped its analysis of affordability in the G7.

The election campaign promise to lower mobile prices by 25% has been delivered, confirmed by the release of the government’s own pricing study. The government’s new benchmarks are seeking a further 25%, rates that are 50% lower than the baseline used in last year’s election campaign. As I wrote in my accompanying article, “Moving the goalposts”, the January 2020 prices being used in the government’s mobile benchmarking are already 10% better than the two year targets that were promised in the run-up to last year’s election.

Today should have been time for the government to take credit for the success of measures it already put in place. The low prices are taking hold across the country (“greater standardization of national MNO pricing across the country”), evidence that all Canadians are benefiting from more vibrant competition.

Facilities-based competition is working; prices are falling; carriers are investing in new new technologies and expanding the reach of their networks.

Declare victory.

Consumers won.