Mythbusting Canadian telecom

A few years ago (ok, maybe 8 years ago), Scotiabank published a report: “Canadian Wireless Myths and Facts”, that gave rise to my blog post “Top 10 myths on Canadian wireless”.

With so much going on in area of telecom policy I figured this would be a good time to update the list and expand it to include more than just wireless.

Policy decisions should be evidence-based, but unfortunately there are a lot of myths that keep being repeated, so much so that some even show up in the media and elsewhere.

Let’s take a look at some of the most common myths. We’ll start with these five, and follow-up with some more sometime soon.

- Myth: Canadians pay more for less

- Myth: Pricing equals Affordability

- Myth: MVNOs aren’t allowed in Canada

- Myth: Government has set a 50/10 minimum speed target for everyone

- Myth: Other countries have a lot more competitors

Whether it’s mortgage payments, the gas bill, or internet connectivity, nobody likes paying bills. The feeling is even worse when you think that someone is getting a better deal. So it’s understandable that Canadians get upset when repeatedly told that they pay more than others for the same or worse service. But like most folklore, it’s not true.

So why do people think this? There are number of international price comparison studies that purport to show that prices in Canada are higher than in most other countries. Unfortunately, most people just read the headlines and do not examine how the study was conducted, what data was used, or critically assess the conclusions. To quote a review of one such study, these price comparisons are often little more than “a careless mish-mash of data points from which no reliable conclusion can be drawn.”

To be clear, there are differences in prices between carriers and between countries. But in addition to using faulty methodology and outdated data, one-dimensional price comparisons make no effort to understand the differences or determine the underlying value that customers are receiving from country to country.

To give one hypothetical example, consider a mobile plan that provides 10GB of data per month with an average download speed of 60Mb/s for CA$60 versus a plan that offers 10GB of data with an average download speed of 3Mb/s for CA$40. Which is the better plan? Based on the methodology of some price comparison studies, consumers would be better off with the 3Mb/s plan because it costs less. That may be true for consumers who don’t use data intensive applications, but for those who do, the $60 plan provides better value.

Another factor to consider is the cost of providing the service. One study found that the cost of building wireless networks in Canada is 83% higher than the average of a group of benchmark countries (Japan, Germany, France, U.K., Italy and Australia) and 34% higher than the U.S.. This makes sense as Canadian network operators, among other challenges, must serve a much lower customer base spread over a wide area, purchase equipment in $U.S., and face much higher spectrum costs.

The point is, price comparisons are meaningless unless one takes into account the plan attributes, quality of service, country attributes and cost of providing the service. While they don’t generate the same headlines, there are studies which take these factors into consideration. For example, a U.S. industry association commissioned a study to compare the value received by wireless subscribers across 36 countries, including Canada. It concluded that Canadians receive more value for their dollar – or “more bang for their buck” – than all other G7 countries plus Australia.

Similar to the previous myth, the term “affordability” gets thrown around without enough consideration of the facts. A couple of months ago, I wrote that the expression has been getting hijacked and applied to alternate agendas, such as ISPs seeking to bypass wholesale broadband access with taxpayers footing the bill for capital investment.

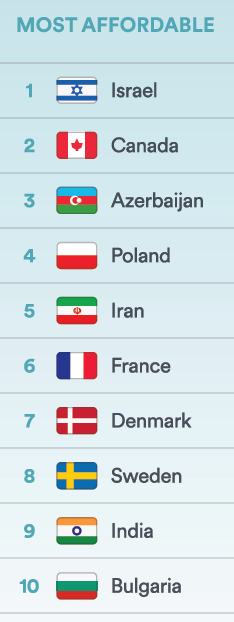

We all want lower prices for everything, but that doesn’t mean that current prices aren’t affordable. To look at affordability, we need to look at price relative to the ability to pay. As I wrote recently, Canadian communications pricing actually ranks pretty well using that metric.

That is certainly not saying that that all Canadians can afford the cost of connectivity, or the devices to connect. Unfortunately, there are Canadians who find it difficult, if not impossible, to purchase mobile devices or computers, and basic internet connectivity. As long time readers know, for nearly 15 years, I have been campaigning and advocating for solutions to this important social challenge.

When people can’t afford necessities such as housing, electricity, food, and dental care, we do not try to resolve the problem by forcing the repricing of these goods and services for the entire marketplace. Instead, governments provide targeted social assistance.

In the U.S., the government recently introduced the Emergency Broadband Benefit which provides a monthly subsidy of between $50-75 that can be used to acquire broadband connectivity. There are also efforts to make such programs permanent.

A similar government program may ultimately be required in Canada, but in the meantime, we applaud the efforts of service providers like Rogers with Connected for Success, TELUS with Internet for Good, and the various carrier partners delivering the Connecting Families initiative.

A similar government program may ultimately be required in Canada, but in the meantime, we applaud the efforts of service providers like Rogers with Connected for Success, TELUS with Internet for Good, and the various carrier partners delivering the Connecting Families initiative.

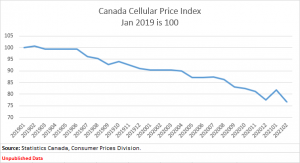

Meanwhile, prices are falling. Statistics Canada data shows that prices for wireless services are continuing to fall while the prices of other goods and services are rising.

Yes, Mobile Virtual Network Operators (MVNOs) should be allowed in Canada. And, (surprise!) they already are.

Indeed, there are a number of MVNOs that have been operating in Canada for years, as well as newer MVNOs like CMlink and CTexcel. Just like most countries in the world, MVNOs are permitted in Canada but, just like almost everywhere, MVNOs aren’t mandated by the regulator.

There are very few countries in the world where the regulator has ordered mobile carriers to make their networks available to MVNOs, and I’m not aware of any regulators that have set wholesale rates. Rather, in the majority of countries with MVNOs, the MVNO must negotiate an arrangement for network access with the mobile network operator. As in all commercial negotiations, there must be a benefit for both parties to the arrangement. This could be through having a well-known brand or reaching a market that the network operator is not targeting. In the end, the MVNO must be able to attract new subscribers to the network operator’s network that the network operator cannot gain by itself.

Over and over I keep reading people say that the CRTC set a minimum basic internet standard of 50 Mbps (down) and 10 Mbps (up) with unlimited download capabilities. A recent ‘Framing Paper’ for a workshop series from Ryerson’s Leadership Lab on ‘Overcoming Digital Divides’ perpetuates the myth that 50/10 is a minimum basic speed.

The CRTC did indeed set a target with those characteristics, but the intent was for all Canadians to have the choice to subscribe to such a broadband service, not a statement that 50/10 is a minimum basic speed that all Canadians require.

There is an important distinction to be made. Some people may choose to subscribe to speeds and capabilities below the infrastructure target; not everyone needs a 50/10 service.

So if you read a report that says X% of households in a given area do not have broadband connectivity that meets the 50/10 target, look closely to see if the report makes clear whether those households do not have that level of connectivity because it is not available or because, for whatever reason, they have chosen not to subscribe to that level of connectivity.

It will be difficult to overcome digital divides if we can’t keep the targets straight.

Some people say that Canada’s mobile wireless market is too concentrated. But what standard are they applying when making these statements?

Of 29 European countries (including the UK), as of the beginning of 2019, there were 19 countries with 3 mobile operators and 10 with 4 mobile operators. In the period between 2010 and 2018, there 4 European countries that went from 4 to 3 mobile operators, and 3 countries that went from 3 to 4. [pdf, 889KB]

In the United States, the number of tier 1 national mobile operators went from 4 to 3 when T-Mobile and Sprint merged in 2020.

Canada has 3 national operators and a number of regional operators that serve different parts of the country.

In addition to the number of competitors, a common measure of market concentration is the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). The HHI is determined by squaring the market share of each firm competing in the market and then summing the result numbers. The lower the HHI the less concentrated is the market.

According to data from GSMA Intelligence, as of 2018, the HHI for Canada was 2518. The HHI for the United States, prior to the merger of T-Mobile and Sprint, was 2664, while the weighted average HHI for the EU was 2966.

Whether looking at the number of mobile wireless operators or the HHI, to say that Canada is an outlier is simply not true.

Which other myths you would like addressed in a follow-up?