Ending regulated cross subsidies

In my view, it is long past the time for ending regulated cross-subsidies.

Three years ago, I wrote “Cross subsidies in a competitive marketplace”. Nearly a decade ago, I wrote “The future of communications cross subsidies”, noting “It used to be so much easier to manage a system of cross subsidies for communications.”

In the old rate-regulated monopoly days, if the regulator wanted consumer services to be subsidized by businesses, rural services to be subsidized by lower cost urban rate-payers, basic local phone service subsidized by discretionary long distance services, Canadian TV production subsidized by cable TV distributors, it could just issue an order to make it so. “So let it be written; so let it be done.” The rates were regulated to ensure service providers had an opportunity to make a resonable return on their investments; consumers had nowhere else to go to arbitrage artifically elevated rates.

As I wrote before, there was a political attractiveness to the communications regulator engineering payment plans for these social benefits. Effectively, these cross subsidies were a hidden tax on communications services, managed off-the-books outside the government tax system. The government could take credit for providing social benefits (lower consumer rates, lower rural prices, increased Canadian content development) without politicians assuming any blame for what would have otherwise been higher taxes to fund these social benefits.

Then, along came competition. Thirty years ago, when long distance competition was first launched, there were explicit fees charged beyond the costs of interconnection – “contribution” (as though it was a charitable donation) – to offset the loss of the excess profits used to subsidize residential phone prices. Rate rebalancing largely reduced these requirements, and a recent CRTC consultation (2023-89) is looking at the evolution of the CRTC’s Broadband Fund.

Today, virtually every segment of the communications industy is competitive. Telecommunications services are provided by countless service providers in Canada and abroad, using multiple technologies, rendering obsolete those regulations that presumed telecommunications over traditional twisted copper wires. Two-way voice (and video) communications are just another app, using analog or digital signals riding on copper, fibre, coax, wireless, or any internet protocol connection. Video services are delivered using regulated broadcast distribution systems or using over-the-air transmission, and people are subscribing to a seemingly infinite array of global streaming services.

How can a system of cross subsidies survive, when consumers are able to choose from service providers that aren’t encumbered by such additional regulated costs?

For that matter, how can traditional broadcasters compete, when there is an imbalance in the burden of regulatory obligations? In a competitive environment, I would suggest that imbalances in regulatory obligations are another form of cross subsidies.

Over the past month, the issue of cross subsidies has come up in two different contexts.

In the first, the CRTC is requiring Rogers to offer a wholesale service to its competitor, Videotron, saying that the financial shortfall can be made up “through other telecommunications services,” all of which are competitive.

In the other instance, an opinion piece in the Globe and Mail says people should ignore concerns about the financial viability of broadcasters because the parent companies are making lots of money in other lines of business:

BCE (which owns CTV, and Noovo in Quebec), Rogers (CityTV) and Quebecor (TVA) complain that competition from CBC/Radio-Canada for scarce advertising dollars is hurting their conventional television networks. Yet, they can hardly plead poverty. Their wireless businesses generate billions of dollars in profits and enable them to cross-promote their networks’ news content on customers’ phones.

It is a ridiculous argument.

A company may choose to subsidize one line of business, if there is a promise of growth and profitability in the near-future. But, if the money-losing line of business is spiralling downward, with its main source of revenue under threat from competitors operating with fewer regulatory obligations, the company will either have to cut costs, find new sources of revenue, or try to shed some of those assets.

The idea that a private sector business should perpetually subsidize a money-losing line of operations with revenue from stronger lines of business makes no sense. A rational business will restructure, or shut down those units that have no opportunity to climb out of the red.

Cross subsidies are simply not sustainable in a competitive environment. Such schemes also cut against Canada’s stated objective of lower wireless prices and increased investment to expand coverage and improve quality. As Dvai Ghose recently wrote in the Globe and Mail, “While the CRTC may have good intentions, it demonstrates naiveté when it comes to the private sector, and the consequences could be incredibly destructive for wireless investment and quality in Canada, risking our ability to compete globally.”

How many contortions will legislators and regulators perform in order to capture all communications services within the so-called “system”?

It is long past time to end Canada’s system of regulated cross subsidies and the market distortions caused by trying to maintain them.

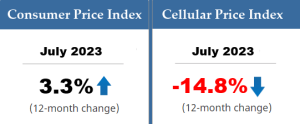

For the past two months, the cellular component of Statistics Canada’s Consumer Price Index has reflected dramatic decreases in prices, approaching a 15% drop year-over-year. These results aren’t really a surprise to those of us who watch the industry and have seen a nearly continuous stream of lower prices, triggered in part by Quebecor’s absorption of Freedom Mobile, and in part the integration of Shaw with Rogers.

For the past two months, the cellular component of Statistics Canada’s Consumer Price Index has reflected dramatic decreases in prices, approaching a 15% drop year-over-year. These results aren’t really a surprise to those of us who watch the industry and have seen a nearly continuous stream of lower prices, triggered in part by Quebecor’s absorption of Freedom Mobile, and in part the integration of Shaw with Rogers.