Let the marketplace work

Canada seems to be afraid to let the marketplace work on its own for telecom. The old “regulators gonna regulate” thing.

A few weeks ago, the Competition Bureau testified at the Standing Committee on Industry and Technology saying, “This committee is well aware that the bureau filed an application to the Competition Tribunal seeking to block the proposed merger between Rogers and Shaw. While we were unsuccessful in our attempt, we stand by our decision to bring the case and our reasons for it.” The representative from the Bureau later said “For example in the Rogers-Shaw case, we would have seen that the four largest firms would have held a market share of 95% collectively.” Was this really a bad thing? Many of our peer countries only have 3 competitors in the telecom market.

The Bureau still talks about Rogers-Shaw as though it should not have been allowed even though the Competition Tribunal thoroughly discarded the Bureau’s arguments. Millions of dollars in legal costs were assessed against the Bureau as a further slap-down of its misguided opposition to the deal. Recall, I cited the finding by the Competition Tribunal, where it stated [pdf, 1.25MB]:

It bears underscoring that there will continue to be four strong competitors in the wireless markets in Alberta and British Columbia, namely, Bell, Telus, Rogers, and Videotron, just as there are today. Videotron’s entry into those markets will likely ensure that competition and innovation remain robust. … Moreover, instead of the two firms (Telus and Shaw) that offer bundled wireless and wireline products in those markets today, there will be at least three (Telus, Rogers, and Videotron).

The strengthening of Rogers’ position in Alberta and British Columbia, combined with the very significant competitive initiatives that Telus and Bell have been pursuing since the Merger was announced, will also likely contribute to an increased intensity of competition in those markets.

The Competition Bureau witnesses only provided a partial picture when saying 4 players have a 95% share. But, this disinformation played well to the expectations of the audience – the Committee MPs.

I already wrote about the faux outrage on display for the telecom carrier witnesses at the committee. As Ted Woodhead wrote, “Most of the MPs on the Committee clearly didn’t care or listen to anything they heard. They engaged with none of it, they speechified, interrupted, some insulted, derided and lectured the witnesses with fact free questions.” Yesterday’s meeting of the Committee was no better.

Many MPs on the Committee simply weren’t interested in fact-finding for their study, ostensibly examining “Accessibility and Affordability of Wireless and Broadband Services in Canada”. Had they been interesting in understanding affordability, there would have been more follow-up on low cost connections, a topic I recently covered in a February blog post.

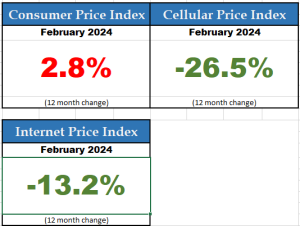

Earlier this year, I wrote “The failure to properly acknowledge the decline in Canadian mobile prices is a form of misinformation, perpetuating a distorted view of the industry. This leads to uninformed public discourse, and misguided policy and regulation.”

The facts are clear. Mobile prices are half of what they were 5 years ago. People get faster speeds, and far more data for lower monthly rates than ever before. Many plans include unlimited calling and messaging. Most service providers have unlimited roaming options available for the US and beyond. Better quality, faster speeds, greater capacity, lower prices. Competition drove these changes. The marketplace is working. As the Canadian Telecommunications Association wrote earlier this week, “in this period of heightened inflation, there is a notable exception – the price of telecommunications services.”

The facts are clear. Mobile prices are half of what they were 5 years ago. People get faster speeds, and far more data for lower monthly rates than ever before. Many plans include unlimited calling and messaging. Most service providers have unlimited roaming options available for the US and beyond. Better quality, faster speeds, greater capacity, lower prices. Competition drove these changes. The marketplace is working. As the Canadian Telecommunications Association wrote earlier this week, “in this period of heightened inflation, there is a notable exception – the price of telecommunications services.”

Still, MPs display faux outrage against the telecom industry. When government policies are set based on electoral calculus, that is a failure to lead.

Carriers are prepared to invest billions of dollars more in digital infrastructure, despite the regulatory uncertainty that overhangs capital markets for the sector.

As I said before, government should declare victory and get out of the way. It is time to let the marketplace work.