Last week, Rogers launched its Screen Break initiative, intended to help Canadian families address excessive screen use among youths.

The Screen Break program was developed subsequent to new research on youth screen time in Canada, surveying more than 1,200 parents and 500 teens and tweens aged 11–17. The research was conducted last October 30 – November 11, using the Angus Reid Forum, an online public opinion community.

The data offers a useful snapshot of how Canadian families are navigating the realities of smartphone use.

The findings will resonate with anyone following debates on digital‑wellbeing. It also identified important questions with respect to expectations placed on telecom service providers.

The most striking gap in the study is perceptual: Most parents see a problem; most youth don’t.

The most striking gap in the study is perceptual: Most parents see a problem; most youth don’t.

- 96% of parents care about reducing or improving screen use.

- 95% are concerned about excessive screen time.

- Only 37% of youth believe they spend too much time on their phones.

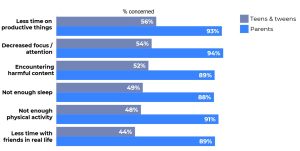

This disconnect isn’t necessarily surprising, but the scale is noteworthy. Parents overwhelmingly believe screen time is harming focus, productivity, sleep, and physical activity for their kids. Youth acknowledge some measure of risks, but nowhere near the same magnitude.

How does this divergence shape household dynamics — and perhaps, public expectations of industry?

Parents are underestimating their kids’ screen time by 90 minutes per day. Rogers’ data shows youth reporting 5 hours and 14 minutes of daily smartphone use, while their parents estimate 3 hours and 44 minutes. That’s an hour and a half blind spot.

For years I have cited Peter Drucker’s principle “you can’t manage what you can’t measure.” How can parents manage their kids’ screen time, when they don’t have an accurate picture of the amount of time in the first place?

And with 89% of youth exceeding a 2‑hour guideline recommended by Canadian health organizations, the gap between parental expectations and experienced reality continues to widen.

The study stops short of claiming causation, but there are consistent correlations between higher screen time and feelings of personal well-being. Youths with 6 or more hours per day report lower overall well‑being, feeling less included or supported in their communities, and being less active physically.

These findings align with broader research: screen time itself isn’t inherently harmful, but excessive use often coexists with other challenges.

A few behavioural patterns stood out from the study. Smartphones account for 49% of all youth screen time — more than laptops, TVs, or tablets. For girls, the study found smartphones represent an even larger share (52%) of total screen time. The study found nearly half (46%) of smartphone use happens in bedrooms, not shared spaces. It’s no wonder parents don’t have a handle on their kids use of devices.

Social media dominates:

- YouTube (22%)

- TikTok (18%)

- Snapchat (15%)

- Instagram (11%)

These patterns are important because location and app mix influence both parental oversight and the nature of the content consumed.

Parents want help; nearly two-thirds (64%) of parents say tools to manage screen time would be helpful. And, subscribers increasingly expect help from their telecom service provider; 62% of parents and 55% of youth believe telecom companies have a role to play in managing screen time.

That’s a significant shift. Historically, responsibility has been placed on platforms (TikTok, YouTube), device manufacturers (Apple, Samsung), or schools. Now, families are looking upstream — to the network layer. This is where the study intersects directly with telecom policy and market strategy, creating both an opportunity and an obligation for service providers.

Implications?

- Telecom service providers are being invited into the digital‑wellbeing conversation. This is not a space the industry has traditionally occupied. The public is signalling openness — even expectation — for telcos to help families manage screen time.

- Network‑level controls may become a competitive differentiator. Parents want solutions that don’t require configuring every device or app. Telcos are uniquely positioned to offer network‑based tools, but must balance functionality with privacy, neutrality, and regulatory considerations.

- Screen time is becoming a public‑health narrative. The correlation between high screen use and lower well‑being will fuel calls for policy interventions. Telcos will need to be prepared for that discussion.

- Transparency matters. The 90‑minute gap between parent estimates and youth reality highlights the need for better reporting tools — and shared understanding within families.

Rogers’ study reinforces what many have suspected: youth screen time is high, parents are worried, and both groups see a role for telecom providers in helping manage it. I’ll have more to say in the coming weeks.

For an industry often criticized for contributing to digital overload, there is an opportunity for telecom service providers to demonstrate leadership — not by moralizing about screen use, but by offering practical, evidence‑based tools that empower families.