Could the CRTC’s latest wholesale regulations stifle competition, precisely the opposite of what was intended?

The introductory section of the decision is filled with puzzling statements, like this:

In recent years, the Commission has noted declining competitive intensity in this industry. The number of Canadians who buy Internet services from independent wholesale-based competitors has fallen by 40%, even as the overall number of Internet subscribers in Canada has increased. In addition, a significant number of wholesale-based competitors have been bought by incumbent companies. When competitors exit the market, Canadian consumers are left with fewer options. It is therefore important that the Commission revise its approach to promote competition and protect the interests of Canadians.

The CRTC seems to believe that the most relevant measure of competitive intensity is by counting the number of smaller wholesale service resellers. The CRTC didn’t look at pricing as a measure of competitive intensity; despite rampant inflation, prices for internet services have declined nearly 8% in the past year according to Statistics Canada’s Consumer Price Index. The CRTC didn’t look at levels of investment; a recent PwC report found “the Canadian telecom sector has invested an annual average of $12.1 billion in capital on network infrastructure. This represents approximately 18.6% of average revenues, which is higher than the 14.2% average across the peer telecoms in the U.S.A., Japan, Australia, and Europe.”

Falling prices and high levels of capital investment are inconsistent with declining competitive intensity.

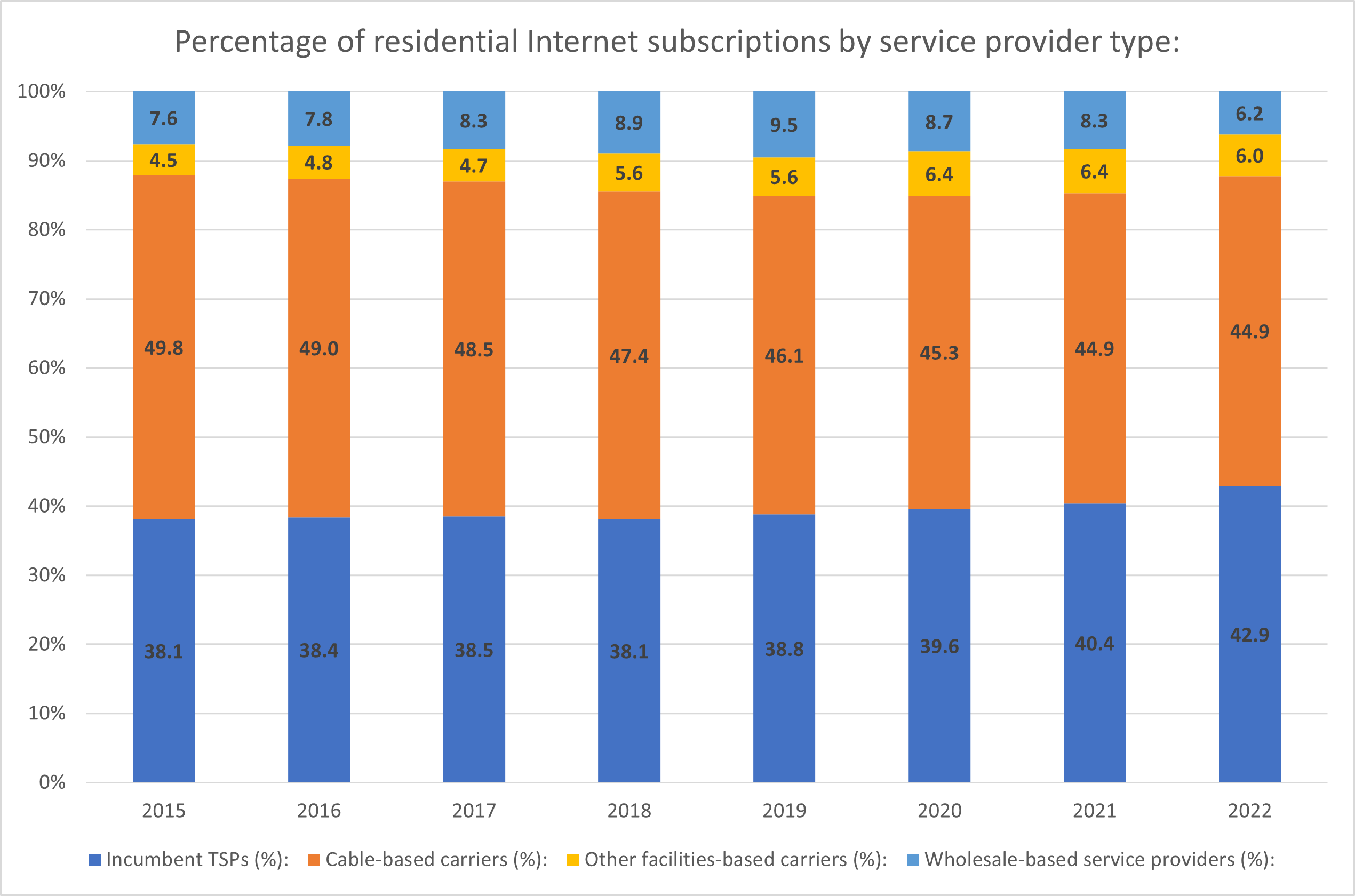

The CRTC claims there has been a 40% drop in the number of Canadians who buy internet services from “independent wholesale-based competitors”. (I am unable to find data that supports the CRTC’s 40% drop in wholesale subscriptions. The CRTC’s Open Data shows that wholesale subscriptions fell 30% from a peak of 1.3 M in 2019 to 0.9 M in 2022.) In any case, this is a small subset (roughly 6%) of the competitive marketplace for broadband services. Let’s look at the CRTC’s own open data (Tab N-I5 of the Data – Retail Fixed Internet table). This chart examines the share of the residential internet market by type of service provider.

The CRTC claims there has been a 40% drop in the number of Canadians who buy internet services from “independent wholesale-based competitors”. (I am unable to find data that supports the CRTC’s 40% drop in wholesale subscriptions. The CRTC’s Open Data shows that wholesale subscriptions fell 30% from a peak of 1.3 M in 2019 to 0.9 M in 2022.) In any case, this is a small subset (roughly 6%) of the competitive marketplace for broadband services. Let’s look at the CRTC’s own open data (Tab N-I5 of the Data – Retail Fixed Internet table). This chart examines the share of the residential internet market by type of service provider.

What we see is that phone companies (termed “Incumbent TSPs”) and cable companies jointly held 87.9% of the market in 2015. That share declined each year through 2020, before moving up slightly in 2021. Newly released 2022 data shows a 2.5% jump in phone company share, largely at the expense of wholesale-based service providers and likely due to acquisitions. The independent wholesale-based segment dropped in 2022 by 2.5% of the market to end the year with 6.2% share. I’ll note that in most cases, the acquired companies continue to operate as flanker brands, so consumer choice has not been reduced.

What is interesting to see is the relatively steady growth in the segment called “Other facilities-based carriers”, rising from 4.5% to 6.0%. Other facilities-based carriers have grown their market share, going from 700,000 subscribers in 2018 to 900,000 in 2022. In other words, we are seeing evidence of the success of facilities-based competition.

The CRTC’s remedy for the declining presence of one type of market participant (wholesale-based) is to require Bell and TELUS to enable resale of their fibre to the home facilities in Ontario and Quebec only. Why Ontario and Quebec only? The CRTC Decision says “The record of this proceeding shows that the competitive presence of wholesale-based competitors has declined most significantly in Ontario and Quebec. These provinces are where competitors have historically attracted the largest number of subscribers, and where they are currently losing subscribers the fastest.”

Duhh. Of course these two provinces “have historically attracted the largest number of subscribers”; more than 60% of Canada’s population live in Ontario and Quebec. Doesn’t it follow that these provinces are where competitors would attract the largest number of subscribers? And it logically follows that where you have the most subscribers would correspond to where service providers would be losing subscribers the fastest. If the CRTC wants to change that state, why is the decision geographically limited? As the CRTC explains in the body of the decision, the Commission still isn’t sure if mandated wholesale access is going to be a permanent or temporary arrangement. “[T]he Commission considers that a narrower scope would reduce the potential impact on both competitors and the incumbent carriers if the Commission later determines that aggregated FTTP access is not required on a longer-term basis or is to be provided under different service configurations.”

In any case, the decision applies only in Canada’s two largest provinces and only to the two largest phone companies, not the cable companies and not the independent phone companies, such as TBayTel in Thunder Bay. In reality, this means the decision has a disproportionate impact on Bell because TELUS is the incumbent local phone company for a much smaller share of the total population, and only in Quebec. But it is worth noting that the cable companies, not the phone companies, are the biggest segment in the broadband market. Resale of gigabit services from the cable companies have been mandated by previous CRTC determinations.

In last week’s decision, the CRTC claims it recognizes and is supportive of investment in facilities.

At the same time, the Commission recognizes that continued investment by incumbent companies is crucial to ensuring that Canadians continue to benefit from robust and reliable Internet services. To achieve this, the Commission has established just and reasonable interim rates that wholesale-based competitors will pay those incumbent companies for access. These rates will ensure that large incumbent companies across Canada continue to have incentive to invest in their networks.

Unfortunately, just and reasonable rates for existing fibre facilities don’t necessarily support the business case for building fibre in new areas.

Even though the wholesale rate may be set to cover the “cost” of the facility, Bell won’t be financially indifferent when a customer chooses a resale-based service provider. Scotiabank estimates that FTTH households have an average $140 per month bundle, substantially more than the revenue associated with a wholesale customer. A major inhibitor of new fibre construction is that the CRTC rejected Bell’s proposal to base the rates on a combination of 5 years of historical and 5 years of forecasted capital. The CRTC set rates based on the historical capital costs.

As Scotiabank recently noted, the average cost per home for fibre has historically been in the order of $1500. This is expected to increase to $2000 per location as fibre plans move to less urban locations. These areas may already have a cable company providing 50/10 broadband and therefore are ineligible for government broadband subsidies. So phone companies look at whether the expected revenues from expansion justify the cost of upgrading to fibre in order to compete against the cable company. With higher capital costs to roll out fibre to less-urban households, the revenue requirements are logically higher. In any business, if the expected revenues from a proposed fibre area don’t provide a reasonable return on the investment, the capital project won’t get approved.

As a result, Bell responded by announcing a cut in its capital program. The capital cuts won’t impact the urban centres; those areas already have fibre. The budget cuts likely will not impact fibre rollout to areas that do not have 50/10 broadband, although there may now be a larger subsidy requirement. As I have written before, the biggest areas of concern will likely be in suburban areas, where the business cases for fibre is most fragile.

I can’t help but consider the irony of the CRTC’s wholesale fibre decision resulting in a reduction in facilities-based competition, the competitive choice of more than 90% of all Canadians.

Is the CRTC choosing to protect competitors when it should focus on protecting competition? Does the most recent decision micromanage some industry participants, attempting to support one group of competitors at the expense of others? To what extent should the CRTC be examining factors to incent intermodal competition for consumer broadband, leveraging 5G for fixed wireless?

The Commission needs to carefully consider whether its regulations stifle competition, and inhibit investment.