I’ve said before that I tend to be a ‘glass half-full’ kind of guy. I like to think that I view situations with optimism as we move forward. There are other industry observers who tend to be more in the ‘half-empty’ camp, viewing the same data with a more negative outlook. And every so often, we run into people who look at that same glass and seem to be unable to see any water at all.

It isn’t just a Canadian telecom phenomenon. Last week, industry critics in the United States seemed to willingly misread financial reports from major carriers and ran headlines like: “It’s Now Clear None of the Supposed Benefits of Killing Net Neutrality Are Real,” [Motherboard] and “Sorry, Ajit: Comcast lowered cable investment despite net neutrality repeal” [Arstechnica]. Both articles were in reaction to Comcast’s financial report last week that showed overall capital expenditures for Comcast’s cable operations declined 3% compared to 2017. Both articles claimed this was “proof” that Ajit Pai’s vision of increased network investment had not emerged from the repeal of heavy-handed Title II regulations for internet service.

However, the commentators made a number of errors in their analyses, the most glaring of which was confusing total capital expenditures with network investment. The Arstechnica article went so far as to quote the Comcast press release, where it was clear: “Cable Communications’ capital expenditures decreased 3.0 percent to $7.7 billion, reflecting decreased spending on customer premise equipment and support capital, partially offset by higher investment in scalable infrastructure and line extensions.”

Unfortunately, the author must not have understood what was meant by those “higher investments in scalable infrastructure and line extensions.” In its 2017 annual report, Comcast said scalable infrafrastructure was increasing network capacity and line extensions are well, extending the lines. In other words, Comcast’s network capital spending has been continuing to rise; its overall capital spending declines because of reduced customer premises spending. The authors of the Arstechnica and Motherboard articles selectively quoted and misrepresented results. Retractions are in order.

On this side of the border, we frequently see similar selective reading of reports. A European consultancy published an international comparison of mobile pricing and usage. Last summer, I challenged the consultancy when it claimed Canada’s mobile data growth between 2016 and 2017 was just 6%, among the slowest growth of all surveyed countries. In the absence of official CRTC published data, it mixed 2016 CRTC results with data it had received from the OECD.

That didn’t keep Canadian academics from citing the flawed study and proclaiming “while Canada’s telecom companies talk about increased usage, the data shows Canada growing slower on wireless usage per SIM than anyone else”. I looked at the flawed data and said the growth rate didn’t pass my smell test.

My view is that bad data should not be used for policy making.

— Mark Goldberg (@Mark_Goldberg) 11 July 2018

Does 6% yr on yr growth in Canadian mobile data use pass anyone’s smell test for 2017/2016?

I doubt it.

I wouldn’t hook my reputation onto someone else’s flawed study https://t.co/k5nCKCqu1w

As it turns out, I was correct. The CRTC’s actual 2017 data ended up showing that data use grew a respectable 37.5%, nowhere near the bottom of the pack.

Last week, that same consultancy released its latest update to the report, continuing its pattern of using old data to represent Canada, and confusing total billing with network service billing. That didn’t stop Canadian academics from again citing the report as evidence of failed communications policy. As I said last summer, “bad data should not be used for policy making.”

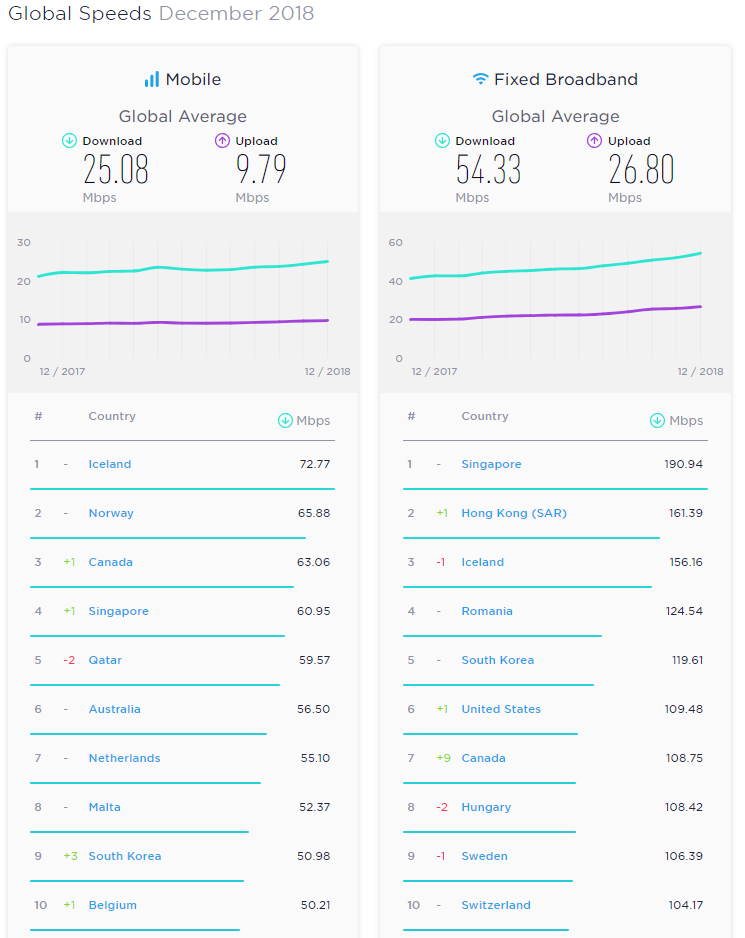

As it turns out, investment in Canadian communications networks is producing measurable results. According to the December 2018 Speedtest results, Canada has the world’s 3rd fastest mobile networks (up from 4th in November) and the 7th fastest fixed broadband (up 9 positions from 16th place in November). An Ookla analysis credits repackaging by Shaw for the recent change, demonstrating quite a sensitivity in its results. [If you want to double-check your internet speed, you can also visit Internet Advisor for a listing of speed tests.]

Too often, writers inject their own bias into articles, and have a tendency to present information in a way that confirms their beliefs. It is called confirmation bias.

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms one’s preexisting beliefs or hypotheses. It is a type of cognitive bias and a systematic error of inductive reasoning. People display this bias when they gather or remember information selectively, or when they interpret it in a biased way. The effect is stronger for emotionally charged issues and for deeply entrenched beliefs.

Sound familiar? As the past week has demonstrated, it is important to read reports with a much more critical eye and seek information from a wide variety of sources.

Better data leads to better policy making.